|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

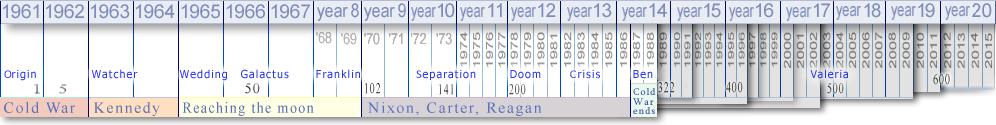

Image: NASA

Date

Significance

Country

Mission Name

August 21, 1957

Intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM)

![]() USSR

USSRR-7 Semyorka SS-6 Sapwood

October 4, 1957

First artificial satellite

![]() USSR

USSRSputnik 1

November 3, 1957

First animal in orbit (Dog)

![]() USSR

USSRSputnik 2

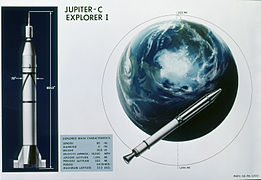

January 31, 1958

First US satellite; detection of Van Allen

belts

![]() USA-ABMA

USA-ABMAExplorer 1

December 18, 1958

First communications satellite

![]() USA-ABMA

USA-ABMAProject SCORE

January 4, 1959

Artificial satellite (Sun's)

![]() USSR

USSRLuna 1

February 17, 1959

Weather satellite

![]() USA-NASA (NRL)1

USA-NASA (NRL)1Vanguard 2

June 1959

Reconnaissance satellite

![]() USA-Air Force

USA-Air ForceDiscover 4

August 7, 1959

Photo of Earth from space

![]() USA-NASA

USA-NASAExplorer 6

September 14, 1959

Probe to Moon

![]() USSR

USSRLuna 2

October 7, 1959

Photo of the far side of the Moon

![]() USSR

USSRLuna 3

April 12, 1961

Human in orbit

![]() USSR

USSRVostok 1

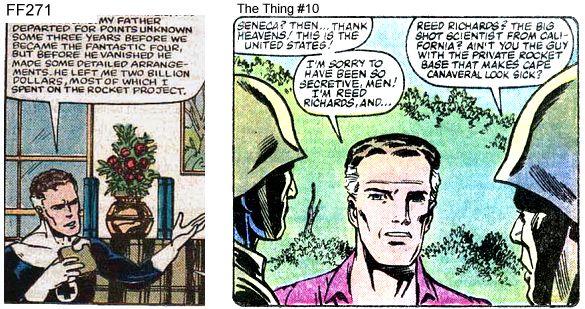

Note the different organizations involved: the ABMA, NRL, Air

Force and NASA. This was not the monolithic NASA that later

controlled the space program, it was the early days when anything

could happen. Everything could rest on a single person or a single

rocket idea. In this period it is highly plausible that a wealthy

scientist like Reed Richards could make a difference.

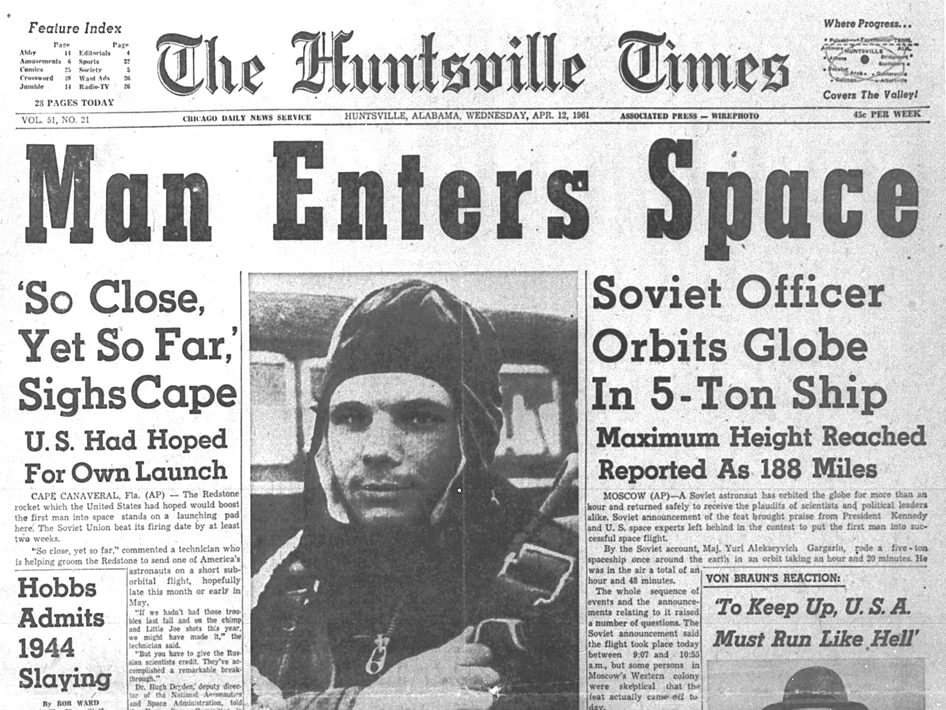

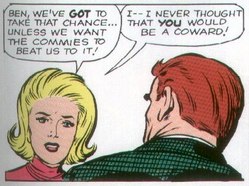

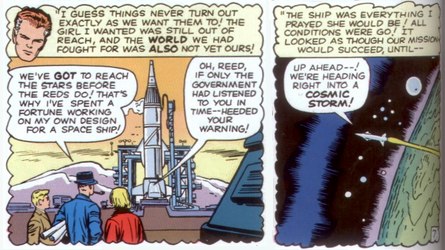

1961 was the height of the cold war, the year that Kennedy was inaugurated as President. Communism seemed to be spreading over the globe. Americans had to show that freedom was best!

Were the Americans really first?

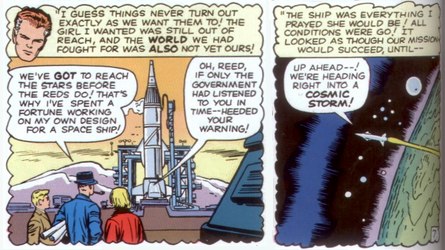

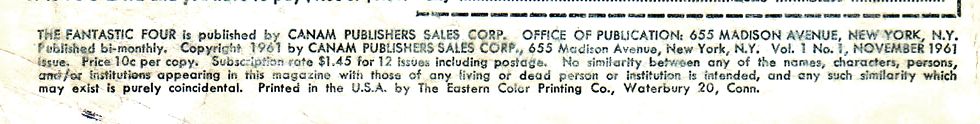

To beat the Russians into space, the origin must have taken place

before April 1961. But the unexpected creation of super powers

made this a matter of military secrecy, so the world at recorded

Yuri Gagarin as being first. The issue was on sale in August 1961

with the next issue in October 1961 (the first issues were

bi-monthly). This allows enough time (April to October 1961) for

the team to become famous, as we see at the start of issue 2. The

stories at this point generally take place in real time, so in

total Act 1 takes around a year.

The Fantastic Four's golden age was the 1960s, up to 1969 when

the first man set foot on the moon: and he was American.

The main Fantastic Four story, 1961-1989, parallels the cold war.

Issue 1 went on sale in August 1961, the week that the Berlin Wall

divided east and west.

The final issue (FF333), was dated December 1989, the month after the

Berlin Wall opened to let people through.

In the early days of the space race, everything could depend on

a single man. In America it was Wernher Von Braun. In Russia it

was Sergey Korolyov.

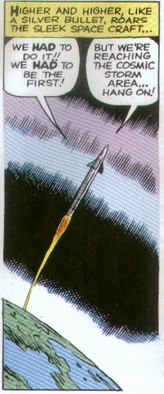

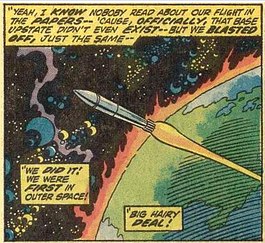

Note that the story only shows them reaching the edge of space,

and no further: just as in the real world. The team did not

wear space suits, and re-entry was not a huge problem. The focus

of the story was just to get to the edge of space and possibly

experience cosmic rays, that is all. Just as in the real world of

1961.

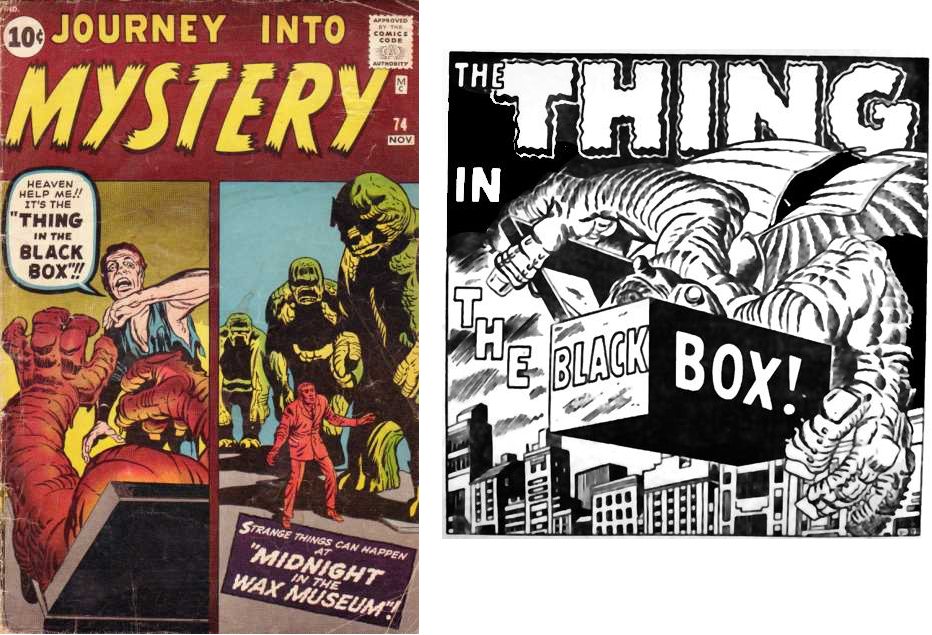

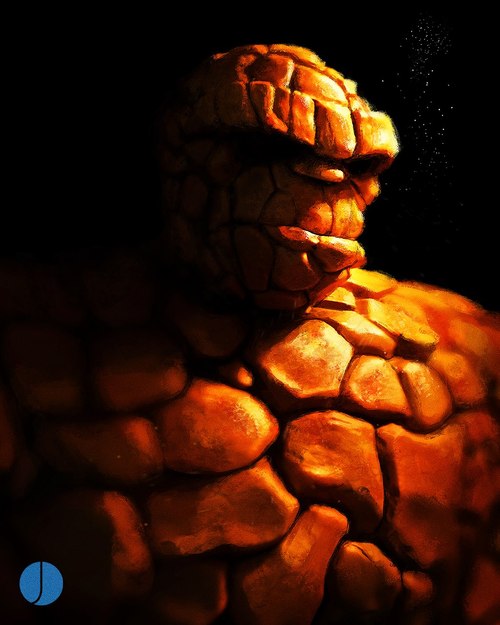

What of the most popular member of the Fantastic Four, the orange skinned Thing?

FF 1 was plotted in April 1961, the month that mankind entered space.

This was a huge leap into the unknown. Within living memory, mankind had

leaped from the horse and cart era to nuclear bombs and space travel.

What would be next?

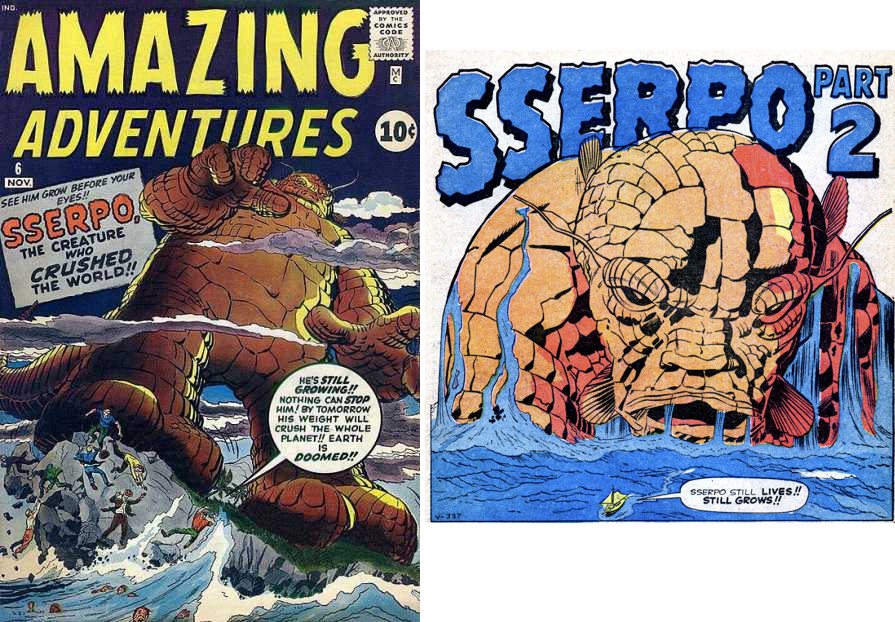

Comics reflect the zeitgeist, and they were full of stories of scientific monsters and great danger. Nobody followed the zeitgeist of the time more closely than Stan Lee and his "Timely" comics. In the month that mankind entered space most of his comics featured orange dinosaur-skinned monsters with names like The Thing.

In the same month, Amazing Adventures had another lumpy orange

monster

that grew ever larger, threatening to crush the world. Once again the

metaphor is obvious: with nuclear power and space travel, and global

superpowers poised to destroy the world, what next?

The idea of a monster who keeps growing, threatening to crush the world, was revisited in Fantastic Four 271. In that issue, years after the paranoia of the cold war, it was revealed that the scientific monster does not in fact crush the world, but the larger it grows the less threatening it becomes. This reflects the essential optimism of the Fantastic Four.

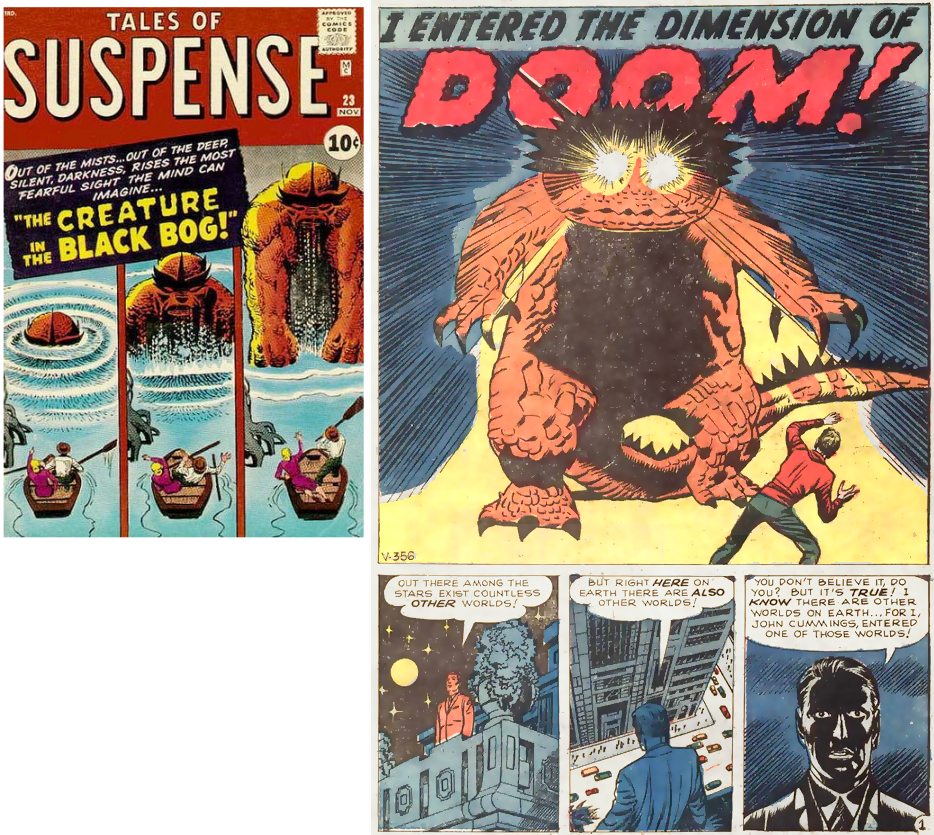

Back to the month of Fantastic Four 1, Tales of Suspense 23 had not one but two

orange monsters. Note the dialog: this is about the scientific and

political world of 1961, where anything might happen: communist

infiltration, new worlds of the very tiny (quantum physics) and very

large (space travel) - what next? As the comic title suggested, people

felt a feeling of suspense at the unknown.

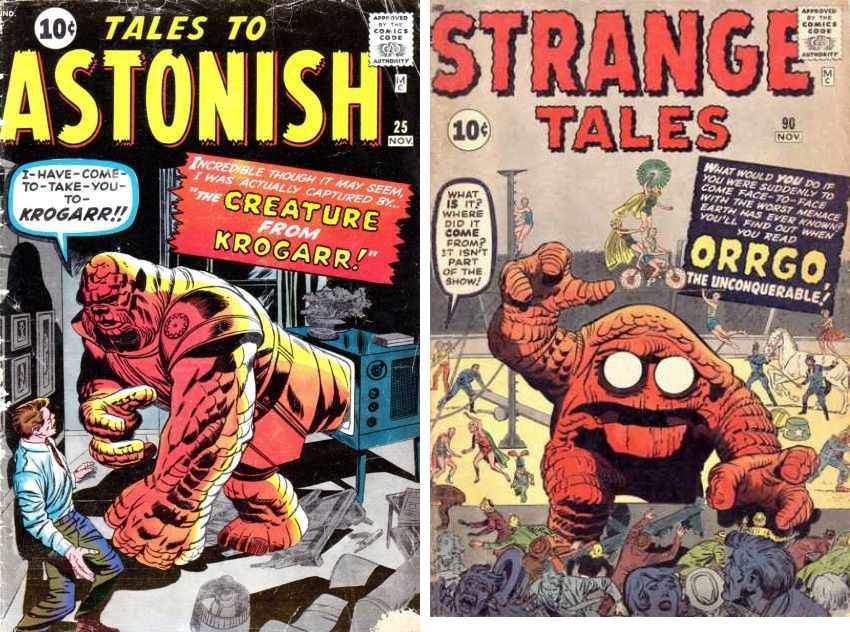

And so it goes on. All of these lumpy orange Things from the same month.

Why the name "The Thing"? It means "the unknown or undefined."

Why the lumpy, rocky hide? This is the skin

of dinosaurs, the only real world monsters we know of.

Why the color orange? This is the color of the mud or earth under our

feet (made brighter for fictional purposes). Dinosaurs are buried in

the earth. The color of the earth suggests great age, weight and

permanence. Contrast this with the usual colors for science fiction,

green and purple, that suggests the ever changing (green for life) and

human social structures (purple for royalty): the use of green and

purple for enemies in comics (as opposed to red, yellow and blue for

heroes) is a topic all of its own. But these orange monsters are

different from the usual science fiction, they represent something

bigger and more permanent.

Which brings us to the final and most famous Thing from this month that gave us space travel: Benjamin Grimm. Why is he remembered when the other Things are largely forgotten? Why did he become the most popular member of The Fantastic Four? Because this orange skinned Thing is different. He is one of us. He will help. He will save us from the green skinned monsters.

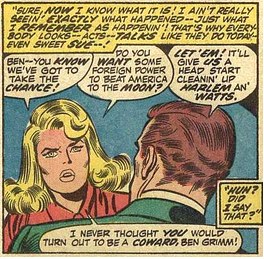

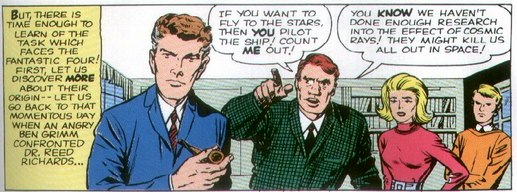

As a test pilot, Ben Grimm is the one prepared for danger. He is the one who warns against the cosmic rays. He is the one with the courage and skill to pilot the space ship. While other comics were afraid of the future, the Fantastic Four embraces the monster, embraces change. Other comics of that month reflected 1950s paranoia, but the Fantastic Four was a message of hope, in keeping with the 1960s.

In April 1961 the first man entered space. Where did the Fantastic Four go?

All the images show them going not much further than the upper

atmosphere, just like Yuri Gagarin.

In FF1, Ben Grimm says "if you

want to fly to the stars..." and that is true: Reed did want to. At the same time,

America was planning to fly to the moon (and then to Mars and the

stars), but for the first eight years all their flights were test

flights. This was the first time the team experienced cosmic rays,

so it must have been an early test flight. In The Thing, issue 2 (in the 1980s), Reed refers to his rocket

as having a "star drive" but

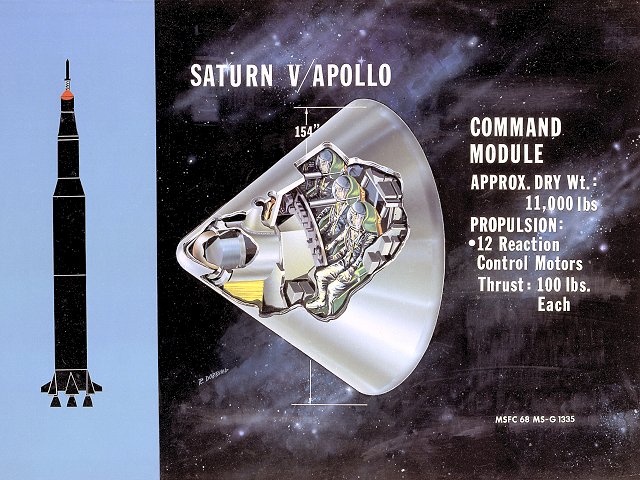

that is just a name. In FF13 they use a "Saturn rocket." But

the Saturn rocket never went to Saturn. The Mercury project never

got as far as Mercury, the Gemini project never got as far Gemini

(the constellation), etc. The context of issue 1 is the US-Russian

race to the moon. This is clarified in FF 126. the goal is not the stars, not

Mars, the moon. And the flight in issue 1

was only a test flight. Just as with the Apollo program, there had to be several test flights before the big one.

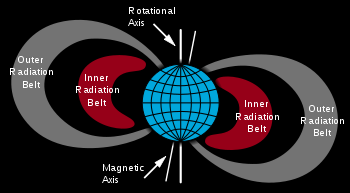

Something like these rays had just been discovered:

From Wikipedia:

"Explorer 1 was launched on January

31, 1958.... It was the first spacecraft to detect the Van Allen

radiation belt."

"Missions beyond low earth orbit leave the protection of the

geomagnetic field, and transit the Van Allen belts. Thus they may

need to be shielded against exposure to cosmic rays, Van Allen

radiation, or solar flares."

Nobody knew exactly what to expect (this was all new), but all radiation was of great concern - this was the height of the cold war, when ever more dangerous atomic bombs were being tested, and the effects of radiation were being discovered.

Russian missions were routinely launched in secret, and only

announced if they were a success - that way they could keep any

accidents quiet. American military satellites are routinely

launched in secret (as far as secrecy is possible with a rocket!)

Reed's rocket base is described as "private" by a guard, yet it cost less than two billion dollars (the moon program cost 23 billion), and is guarded by the military.

Obviously the Pentagon would resent it when Reed used his money to gain influence. There seems to be some tension here, a feeling of "them and us."

| Location | Operational date |

|---|---|

| Wallops Flight Facility, Delmarva Peninsula, Virginia | 1945– |

| White Sands Missile Range | 1946– |

| Nevada Test and Training Range (formerly Nellis Air Force Range) | 1950s– |

| Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida | 1956– |

| Vandenberg Air Force Base, California | 1958– |

| Kennedy Space Center, Florida | 1963– |

| Pacific Missile Range Facility, Hawaii | 1963– |

The exact location would be a secret, so would be reported in the comic as either New York or California to throw people off the scent.

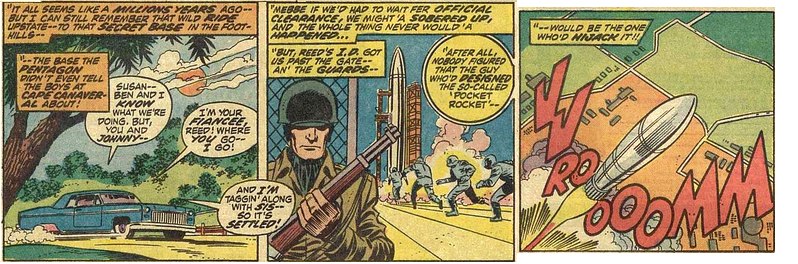

Reed designed the ship, so had clearance at every level. The rocket was fueled and ready to run. The only conflict was delays due to concern over cosmic rays. Top brass was cautious, and Ben Grimm (the pilot) agreed with them. Reed was tired of the delays, saw a launch window in the weather, and decided to launch right then. Is that really so unlikely? Is he the first military man to ignore red tape and take a risk to get things done?

A launch requires time, and a support team on the ground. Obviously Reed would have his own technicians for ground control: the men and women who have worked under him for years. The story is merely a red tape issue, nothing more.

The Apollo program was typically designed for three astronauts,

and Reed's rocket was no different.

He obviously planned for later expansion, so added an extra seat in front.

Four people was not too much weight.

The early test flight was only to enter space and go no further. The rockets are designed to carry

many tons of fuel. By choosing a shorter flight the amount of fuel

can be slightly reduced. With fewer tons to carry the test rocket could easily take an

extra passenger.

Why take Ben?

Ben was a test pilot, and needed to fly the rocket. As 'Iron Maiden' noted, "Ben was a test pilot after the war

(think Chuck Yeager type) and most of the early astronauts in

the RW were Air Force or Navy pilots. In fact the president

insisted all the Mercury 7 astronauts had to be test pilots.

Jack Kirby or Stan probably would have been aware of that since

the space program got quite a bit of press compared to today. In

Sci Fi movies of the time, it was common to have civilians on

board whatever vessel was dreamed up for the movie. But let's

just say Stan and Jack were ahead of the curve their since

civilians have been on trips on the various space shuttles

before their retirement. Probably the only crew needed were Ben

and Reed, who was part of the project."

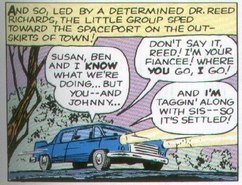

Why take two more passengers?

This was a test flight, and had room for four people. More people meant more data to study.

Why take Sue?

Why would Reed try to impress his girlfriend? Men trying to impress

women is the story of the human

race. What could be more impressive than being the first man in

space and taking your girl friend with you. Besides, a test flight is

designed for gathering data. It would be very interesting to compare

male and female reactions.

Why take Johnny?

For the fourth test subject Reed needed somebody he could trust. The

fact that Johnny, being younger, weighed less, was a bonus. His youth

made him more interesting to study: the more body types the better. As

for leaving him home that might be impossible. Johnny was a teenager who

loved engineering more than anything. He would kill to be aboard this

machine. And whereas Reed was a designer and Ben was a pilot, Johnny was

the only one with daily engineering experience. Early spaceflight was

"flying by the seat of your pants" where the ability to tinker could

save your life.

And finally, young people have far better eyesight than adults. A

fifteen year old's eyes might be a real asset in the darkness of space.

Evolution depends on random variation, caused by random changes to DNA, some of which is caused by... cosmic rays. As Wikipedia explains:

"Random mutations constantly occur in the genomes of organisms; these mutations create genetic variation. Mutations are changes in the DNA sequence of a cell's genome and are caused by radiation [and other causes]"

Traveling in space, or even in an airplane, increases your exposure to cosmic rays, and thus the mutations caused by comic rays. Some of these will be beneficial, more will be harmful, but most will have no noticeable effect. The question is not what happened (cosmic ray mutations are perfectly normal), but how it happened: how quickly, and so dramatically.

The only question with the Fantastic Four is one of scale: could such great changes happen that quickly, and if so, how likely is it to cause good rather than bad results?

The characters first assume that cosmic rays caused their superpowers. As they learn more, that conclusion changes: other phenomena were involved too.

The Fantastic Four is based in realism, so they immediately saw something was wrong: Yes, cosmic rays can cause beneficial mutations, but the odds against such extraordinary mutations are impossibly high. "It's almost as if it were pre-ordained."

This was no accident. America is a religious nation, so the Great

American Novel hints of a higher power behind this. For details

see the page on the cosmic. This was the Americans' destiny.

Above all, the Fantastic Four is about the fantastic. Yet every concept is based in some way on the real world. Even the disappearance of buildings into huge holes, in issue 1. Ever heard of sink holes?

I can't resist showing this Photoshopped image by the "mbworld" moderator called "nola"

This is just one of many elements from the Fantastic Four that years later show up in Star Wars. The best known example is Dr Doom, foreshadowing Darth Vader. See the notes to FF17 for more details.

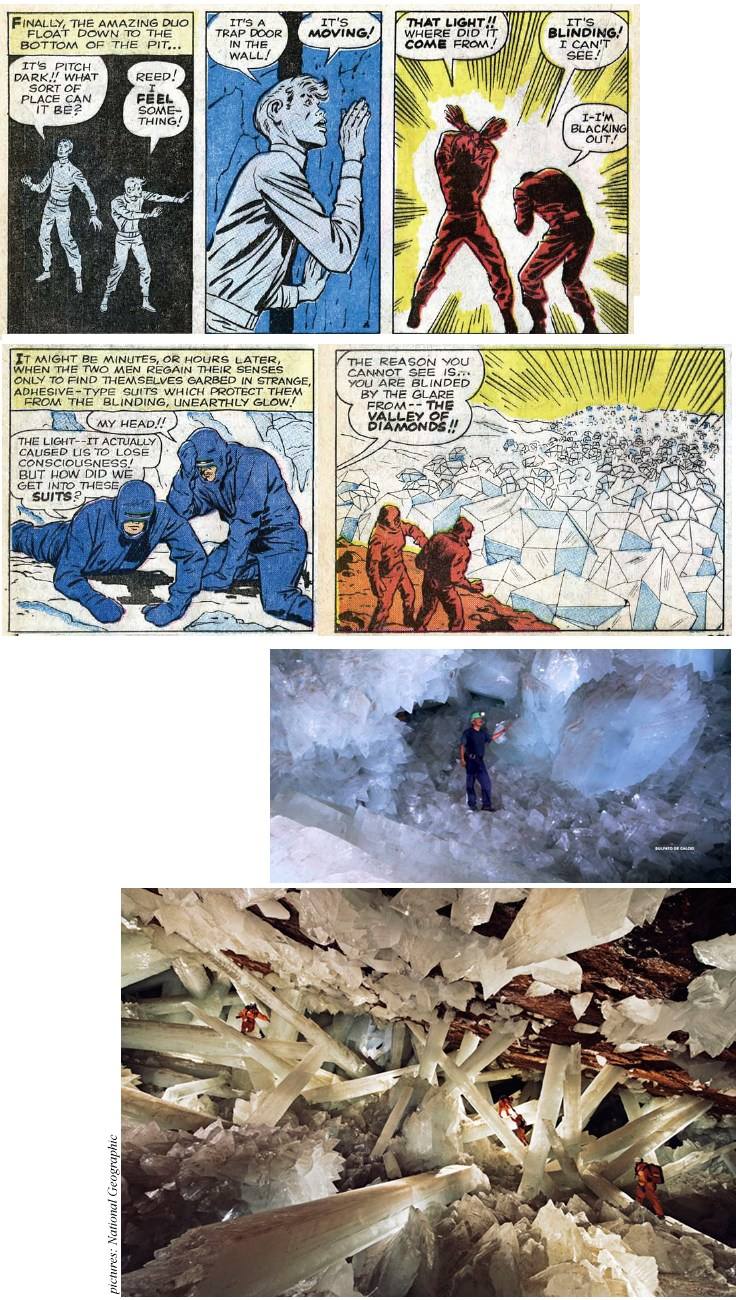

Often the comic is years ahead of the real world. Here for

example is the underground valley of diamonds from issue 1, dated

November 1961. Compare the real cave of Crystals discovered 40

years later

Note the people in the second picture: this cave is even bigger than the one in the comic.

Anything fantastic is fair game if it fits the world of science.

In the next few months the Fantastic Four conquer every frontier:

under the ground, the oceans, the far corners of the earth, and of

course, outer space. All through scientific breakthroughs.

The science of underground empires

Some readers cannot get past the idea of an underground empire. but while exceedingly unlikely, it is possible, and in an alternate timeline could have happened, like this:

And so an underground empire is entirely rational, if we just think about it.

Issue 1 contains two stories: the origin, in space, and the battle under the ground. It symbolizes the fall of Reed's impossible goals, the overarching theme of the next 321 issues. it also shows how the team encompasses everything from the skies above to the earth beneath.

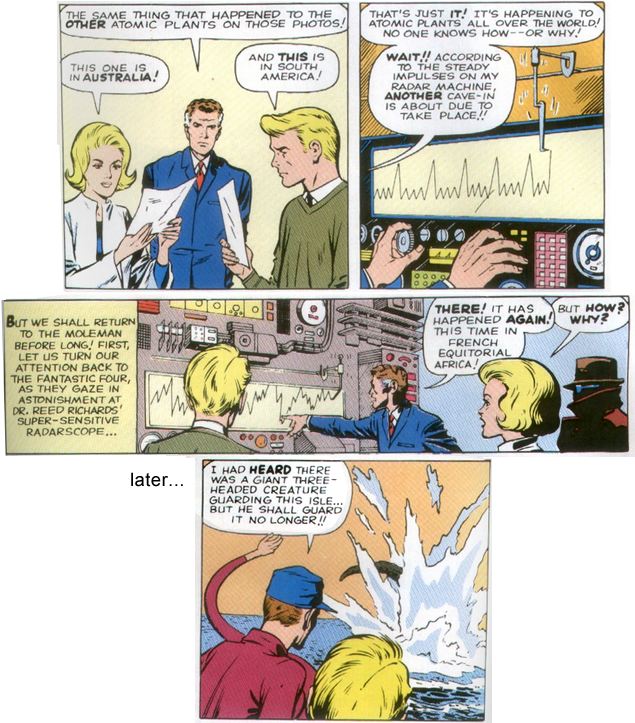

Both stories are about the space race

The Mole Man story may not seem to be connected, but look

carefully: Reed learns of the Mole Man because he is monitoring

two sources of information

The Mole Man is discovered by accident: the purpose of this

equipment is plainly to assess a foreign power's technology.

Nuclear power was cutting edge back then, and radar and seismology

were the only way to detect rocket launches. Note that Monster

Isle, while officially placed in the Pacific (FF296), is placed in

the Bermuda Triangle in Walk Simonson's run (the famous "new

Fantastic Four" issues). The simplest explanation is that during

the cold war its location is a state secret. After the cold war

its real location could be revealed. In April 1961 the Bermuda

Triangle meant one thing: Cuba. April 1961 not only saw the first

man in space but also the Bay of

Pigs fiasco. In another year we would have the Cuban Missile Crisis. Monster

Isle works as a metaphor: What monsters do the Americans fear?

Where is their island? And how do they operate? Underground of

course. The Cuban Missile crisis was about nuclear weapons (hence

the interest in nuclear plants in the story) but this cannot be

separated from the space race. In 1961 they both used the same

rocket technology and they were both attempts for each side to

intimidate the other.

So the overriding objective of the team in both stories is the cold war, and the development of rocket technology. This is the purpose of the team in issue 1. The space race was not decisively won until the first man on the moon, in 1969. This was recorded in FF98. In effect, the first 100 issues are about the space race.

Imagine what that is like to be the Mole Man, hiding underground,

being the most miserable and lonely of all men, believing that every

single human was evil. His only friends are the simpler humanoids around

him: they were loyal and (relatively speaking) loving. He would come to

see them as the true humans, driven underground by the monsters above

ground. When he then saw humans develop nuclear power and rocket ships

he would see them as an existential threat. What was he to conclude? The

story says he is driven mad - the pressure on his mind reflects the

pressure of all those rocks above him - something had to give. I think

that any of us would be the same under that immense pressure.

Immense pressure is a metaphor for the psychology of the 7 year story.

All of the team were trapped in some way. Ben was trapped as a monster,

Johnny was trapped by his loyalty to the team (he could not be

independent or follow Crystal), Reed lacks social skills: nothing as bad

as Moley, but he was still unable to get what he wanted, as he lamented

in issue 9. And finally Sue never wanted to be a superhero, she just

wants a quiet family life and polite society, yet finds herself in

violent battle after battle. They have the power to reach for the stars

(literally and metaphorically) yet are weighed down by their own

down-to-earth pressures.

Issue 1 starts with Ben gong underground to hide, in the sewers: symbolizing how he feels dirty. The water also symbolizes uncertainty and instability: issue 2 again begins with be submerged in water. Then in issue 4 he takes a bomb to destroy the water monster (symbolism again!) and in issue 5 decides that living on the water is not such a bad idea, showing how he is working through his inner feelings. Underground river explicitly link to inner psychology in issue 248 (248-256 focus on Reed's mental state) and 314-15 (314-319 focus on ultimate resolution and answers: note how the water motif changes to an ice motif, suggesting the instability has been tamed and become timeless like the earth).

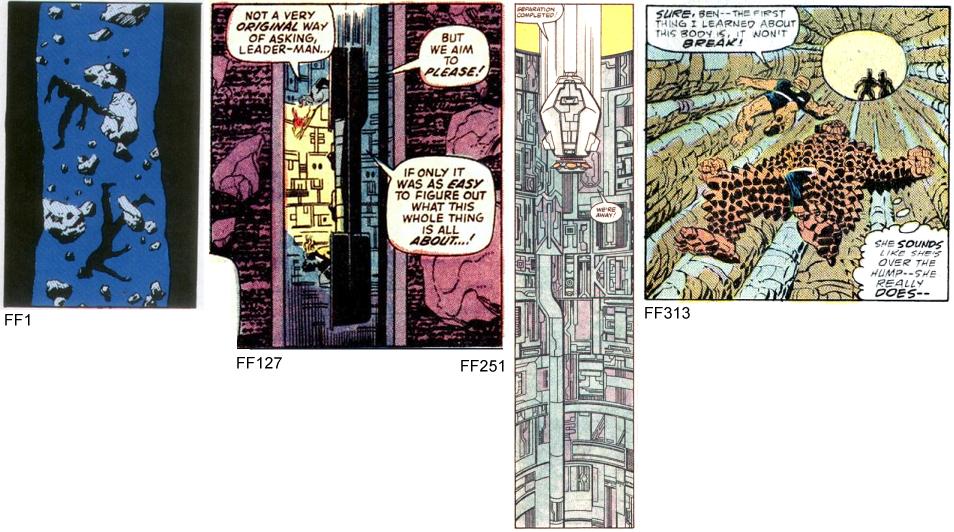

For the symbolism of plunging down a shaft (it happens at four key

moments in the 28 year story) see the notes to FF127. The whole 28 year

story can be seen as coming down to earth: they think their threats are

from the skies (aliens, representing Russian missiles) but the real

problems are within: if they are strong as a family then nothing can threaten them.

The whole point of the origin is the space race, which began at the

start of the 1960s (first man in space) and ended at the end of the same

decade with the first man in the moon. The Fantastic Four uses the moon

to symbolize the future at key points

These reviews will often have a section on "objections." Looking at

apparent weaknesses is a good way to uncover the underlying strength of

the novel.

The big Fantastic Four story is is all about the Negative Zone,

and it starts here. The dimensional portal (i.e. the negative zone

portal) is the background to the Mole Man story. It is also the source

of the team's powers. Here is the proof:

In FF annual 6 we learn that Sue's body, and hence Franklin's body, can

only be regulated using material from the Negative Zone. This suggests

that their powers came from the negative zone, but how does that fit

with issue 1? The powers are first explained in FF 197: they came from

very specific cosmic rays caused by sunspots. These rays are almost

certainly positrons. Positrons are the antimatter (i.e. negative zone)

counterpart of electrons. These are present in cosmic rays, particularly from solar flares (i.e. they are associated with sun spots).

Only one story deals directly with solar flares or anything like them:

FF 297, exactly 100 issues after the sun spot revelation. It is also

first story of act 5 (after the anniversary issue), the act where

everything is explained. In FF 297 a dimensional portal is siphoning

power from the sun, and the only way to counter it is to produce an

opposite siphon. when this positive and negative flow meets it creates

an "infinity vortex" with the power to combine two people into one. This

ability to combine people explains the teams powers:

Johnny:

In FF 132 we learn that Johnny was a fan of the original Human Torch, and gained his powers: in effect the two people mix.

Reed:

The same issue suggests that Reed's power also comes from his reading

matter: he was probably a fan of The Thin Man (see my notes to FF 132).

Sue:

The young Sue was a fan of prince Namor (see the notes to FF 291), the

most powerful man on the planet (due to his mixture of physical

strength, ruling the world's biggest empire, and his advanced

technology). Namor's general purpose power is reflected in Sue's general

purpose force.

Ben:

Ben grew up as a fan of tough street gangs, so became the toughest one

of all. But street gangs are trapped by their environments, and so was

Ben.

So we see that the powers probably came via positrons via a sub-space

portal created by the sun's gravitational field. The negative zone

portal is of course another name for the sub-space portal. For how two

people from different times can mix their abilities, see the discussion

of time travel by FF 187, and in the notes to FF annual 16 (about how

Ral Dorn mixed with Aron). Thanks to Nathan of "how would you fix" for

first suggesting positrons. And note how positronic brains are the key

to the most famous science fiction story about human progress: Isaac

Asimov's "I, Robot".

"Reed and Sue" from "Ralph and Sue"?

"My DC-loving friend likes to point

out that a lot of Marvel characters are just copies of DC predecessors

(his favorite go-to argument being that Peter Parker is essentially just

Clark Kent - working at a newspaper, wore glasses, masquerading as a

weakling, etc.).

Recently he pointed out that

our Reed and Sue made their first appearance about a year after Ralph

and Sue Dibny were already created in the pages of Flash. To the ear,

Reed and Sue sounds a lot like Ralph and Sue, and of course, both Reed

and Ralph are stretchers (although both were introduced a couple decades

after Plastic Man)." ("Unstable Molecule", on the FF message board)

For many more examples of Marvel copying DC, see FF 36 and the discussion of Medusa and Spider Girl and other examples

All the themes of the 28 year history are introduced in

issue 1.

The obvious themes are

Then there is the act by act themes: each is present in every act, but in each act one dominates:

These major themes should be obvious in every issue, so they won't be

discussed much on this web site. Instead we'll concentrate on

secondary themes.

The themes form conflicts, and these will all be resolved (or close to resolution) by issue 321:

As this is the Great American Novel, these are also America's themes:

The zeitgeist

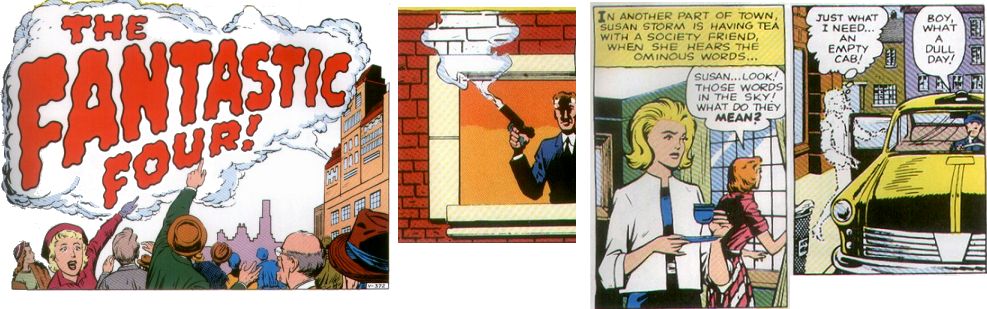

The story is straight from the zeitgeist of 1961: the first American in space, the rise of nuclear power stations, the height of the cold war, and the height of the fear of enemies undermining the nation and the world. Issue 1 is basically the American zeitgeist come to life. The characters represent American ideals of the time: the serious determined scientist, the simple fighter, the pretty socialite, the kid playing with hot rods. The Bay of Pigs invasion is reflected in the Fantastic Four invading Monster Isle, the base from which an underground empire could threaten any nation on earth, just as the communist island on America's doorstep caused the same fear. The Fantastic Four appeared to succeed, but like Castro, the Mole Man did not go away, he later came back and blamed the FF for the damage to his island.

Foreshadowing the final issue

The story begins with a race for the moon (as a step to the stars), and the story will finally end (e.g. in Stan Lee's "The Last Fantastic Four Story") with the same image, this time in triumph, with the team probably leaving to collect Crystal and begin a new era.

Remember:All this detail was unplanned!The story parallels the real

world only because

the The story evolved a long term

structure only because

The story is rich and complex

only because |

The super powered stuff is not the heart of the story. There are

no stories about

stretching or flaming. Powers are merely a McGuffin, a convenient

way to tell other

stories.

Three dimensional characters

The real story is the characters. At first glance they may seem

shallow, but look closer. Take the Mole Man for example. It's not about

monsters. It's about loneliness. The monsters are how he sees his fellow man.

Science fiction is always about us. It lets us examine our own interests by painting them in brighter colors: wild stories can contain more reality than mundane stories. They allow a wider range of real world issues, more locations, more emotions, a wider range of people, and more possibilities.

I love the moral dilemmas faced by, say, Franklin Storm or the original Gremlin. I love seeing how Sue reached people (like Dragon Man) that more violent people cannot. I love reading about micro worlds, ancient worlds, and exotic places like New York (I live in a small Scottish village). The FF introduced me to Prester John, antimatter, disabilities, alien points of view, and so much more!

The situations are soaked in realism. Take Galactus for example. We may never face Galactus but we will face problems of a similar magnitude, and that's what makes it real. The comics described how ordinary people react (some blamed the heroes, some denied it happened, others just didn't know what to think), how advanced beings saw it (who has a right to exist, and at what cost?), how the heroes felt ("we are just ants"), and so on. The McGuffin of a fifty foot giant and a spaceship were almost irrelevant to the story, except that the space race was real and belief in gods was real. Whenever I re-read those stories the realism knocks me over.

As Neil Gaiman said (after G.K.Chesterton), "Fairy tales are more than true — not because they tell us dragons exist, but because they tell us dragons can be beaten."

The dragon is not the point: it is almost irrelevant. it is simply the fastest way to summarize all the very real dangers that exist. And if it then turns out that other kinds of dragons are real (Komodo Dragons, Dinosaurs, the possibility of future genetic engineering, legends based on an actual serpents, etc), and at the time it seemed still possible that maybe that kind of dragon was real as well, then the dragon becomes an additional link to the real world, a window on new possibilities, a path worth exploring in order to open up the real world. The dragon therefore adds to the realism.

What is real? What matters? Without going into philosophy, questions of correct behavior are real. They are the basis of society and friendship, without which we could not survive. The Fantastic Four provides this reality through comics as morality plays.

The original medieval morality plays were very much like superhero stories: larger than life characters who personified moral attributes. The earliest Marvels are full of such characters. I'm not saying that they were designed as morality plays, but a good moral is just a natural part of a larger than life feel good story, and these were very much larger than life and very feel good. Just about every issue had some bad guy representing some moral failing and we see how that failing leads to their destruction, whereas the good guys extol friendship and overcoming their differences and triumph. Some of the bad guys could have come straight off a medieval stage: the hate Monger, Psycho-Man with his tablets with the words "hate, fear, doubt" in big bold letters; Doom's foolish arrogance, the Red Ghost's mis-placed patriotism, etc. At the time of writing (August 2011) this month is FF issue 8 (now the "Future Foundation"), and I was re-reading the original FF issue 8 ("Fantastic Four"), so let's start there:

FF8: the Puppet Master tries to control people for his own benefit, and ends up apparently killed by his own greed. A very moralistic last panel shows the broken doll on the ground.

The previous month, FF7, was the first FF issue I ever read as a child, and shaped my view of comics. Here the sin is lust for power: Kurggo, master of planet X, is left clinging to his previous gas canister that would make him master of the world. Because of his love of power he ends up missing the ship that takes his people to safety and we see him lying amid the rubble, a victim of his own greed. It was powerful stuff - well I thought so anyway.

The month before, FF 6, showed how bad guys never look after their friends: Namor teams up with Doom, Doom betrays him, and Namor realizes who his real friends are. Yes it's a simple and familiar message, but that's what morality plays are for.

The positive messages go well beyond simply using super powers: they defeat Dragon Man by becoming his friend; they defeat the Impossible Man by ignoring his foolishness; they defeat the Miracle Man by choosing to not believe in him; they defeat the unnamed Thing impostor by their good example, and so on. At their peak, the late sixties, they were always saying slushy things about love and faith and hope, and if it wasn't clear enough the Silver Surfer would preach at every opportunity. I could go on and on. Ditko's Spider-Man was the same: he had a message. Not as over the top as the later anti drug issues, but Ditko made no secret of his beliefs and how his stories spoke for him. They didn't always hit you over the head with the message, and they were seldom planned, but the message was always there.

FF 1 contains numerous moral messages, including:

Much of this is standard superhero stuff, but they did it with added realism: they fight and argue and do sensible things lie forgoing any secret identity.

But does this increased reality balance the loss in reality from having giant monsters and space ships? Yes, it does, because the giant monsters and spaceships, while highly unlikely, are perfectly possible. An example of this heightened realism is in his realistic character, discussed elsewhere. Here we will just look at the science.

Claim 1: people can live at the center of the Earth.Reality: the comics use this as hyperbole. If you read the stories they seldom go more than a mile or two down, so the actual claim is that people can live in caves. That is based on reality.

Claim 2: a human could live for much of his life in caves.Reality: this was common for our ancestors, when caves are available they make ideal homes. We know that fungi can grow without light, so it is realistic to speculate that perhaps a person might live for extended periods underground, only emerging occasionally to gain whatever supplies are not available.

Claim 3: surprising and unexpected things can exist.Reality: surprising and unexplained things are discovered all the time, and this as especially true in the period leading up the 1960s. Obviously we don't know what the surprises will be. For example, it was not until the 1920s that most people accepted other galaxies existed. Around the same time, people were learning that time and space were far more amazing than anybody ever expected. The idea of giant monsters living underground was no stranger than that. The job of speculative fiction is to explore the possibilities: books speculated that the universe might be vast, time travel may be possible,monsters may live in caves under the ground, etc., etc. and some of these things are proven right and some are not. The only unrealistic fiction is that where nothing amazing and surprising ever happens.

Claim 4: giant monsters, giant machines, and all the rest.The existence of advanced aliens is what

matters. Once that is established then everything else

follows in a very mundane fashion. Any civilization that is merely

a few thousand years more advanced than ours would be able to

perform endless miracles, fill every space, and make use of

resources (like underground rocks) in ways that seem crazy to us.

And if they left behind a space ship then obviously our best

scientists would work out as much as they can about how it works,

and use it. So all the other stuff becomes very ordinary once the

alien part is sorted.

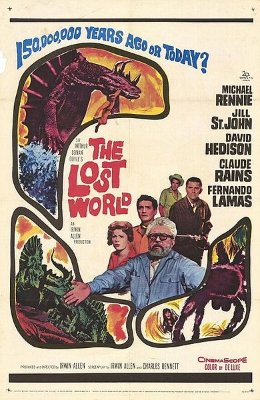

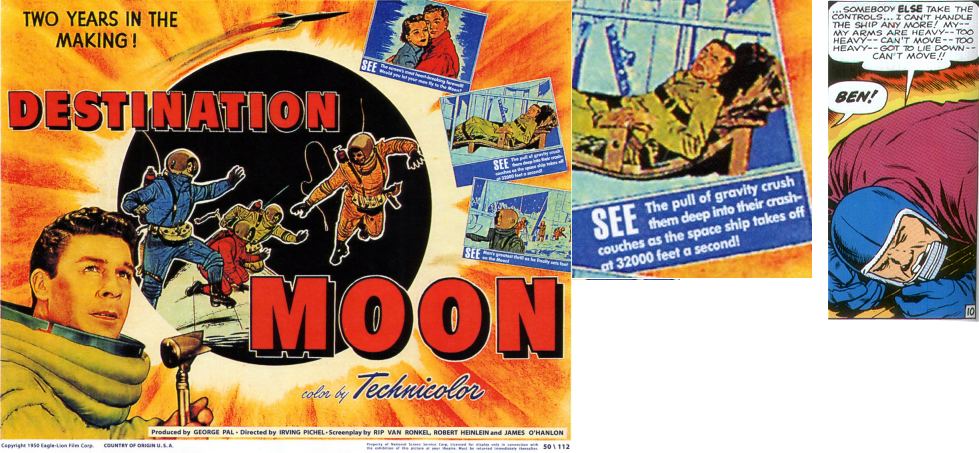

"There used to be a very popular Sci Fi sub genre/trope called (by TV Tropes at least) The Lost World trope. In it, some motley crew of explorers of some sort stumble onto an island of monsters or lost civilizations or some other sort of uncharted territory full of danger, like monsters and lost tribes or weird mutated races. [The Lost World movie was released in 1960, and FF1 came out in 1961.- Chris]

"Sometimes the motley crew are explorers whose job it is to discover new things. Other times it’s just a group of people traveling together who get forced into the role of explorers accidentally by crashing onto an island or something. There was usually a handsome, dashing heartthrob scientist type (back before modern fiction decided that all scientists had to be borderline autistic nerds), the big galoot muscle, the Gal Friday/Love Interest and the kid sidekick, who usually pals around the most with the big galoot. Sometimes there are a few more characters but you usually have that core four. Another way to look at it is THE 4 archetypes: Father, Mother, Clown Child, Gifted Child. Mark Andrew did a great piece here posing the theory of how Fantastic Four #1 reads like a Lost Worlds type monster story re purposed as a superhero story at the last minute.

"You can see this structure to some degree in other books that were part of that Explorers of Lost Worlds trope, like Challengers of the Unknown. Metal Men had some of the same dynamics. Reed Richards and Gilligan’s Professor (along with Metal Men’s Will Magnus for example) are perfect examples of the Dashing Heartthrob Scientist and the Father archetypes, which is why I think so many people subconsciously associate the two characters with each other. Also, the Lost World Explorer genre is pretty much dead, so two of the only examples of it that still remain prominent in the minds of modern audiences are Gilligan’s Island and Fantastic Four (and arguably the TV show Lost). Since Gilligan’s Island and Fantastic Four are the only two Lost Worlds properties that most modern audiences are well acquainted with, it’s easier for them to believe that there is some significant connection to them and to think their similarities are more significant than they actually are, but at the time when Lost Worlds was a really popular genre there were countless interchangeable Reed Richards/Professor types." [Alex Ross used the Gilligan Professor, actor Russell Johnson, as the model for Reed in "Marvels."]

On the subject of Doc Savage...

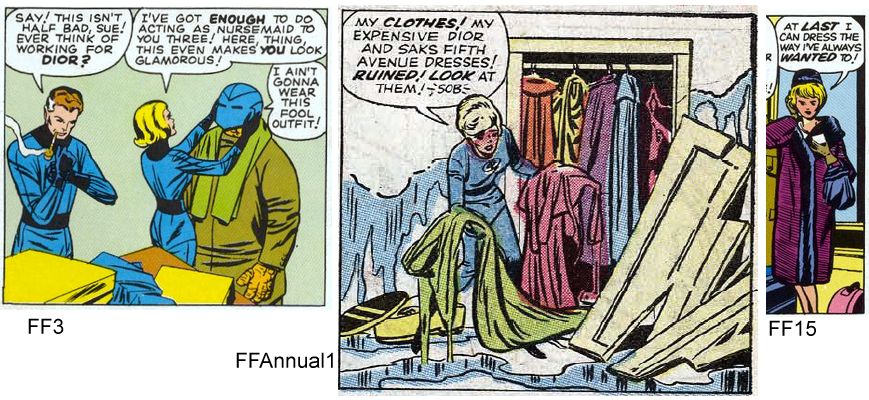

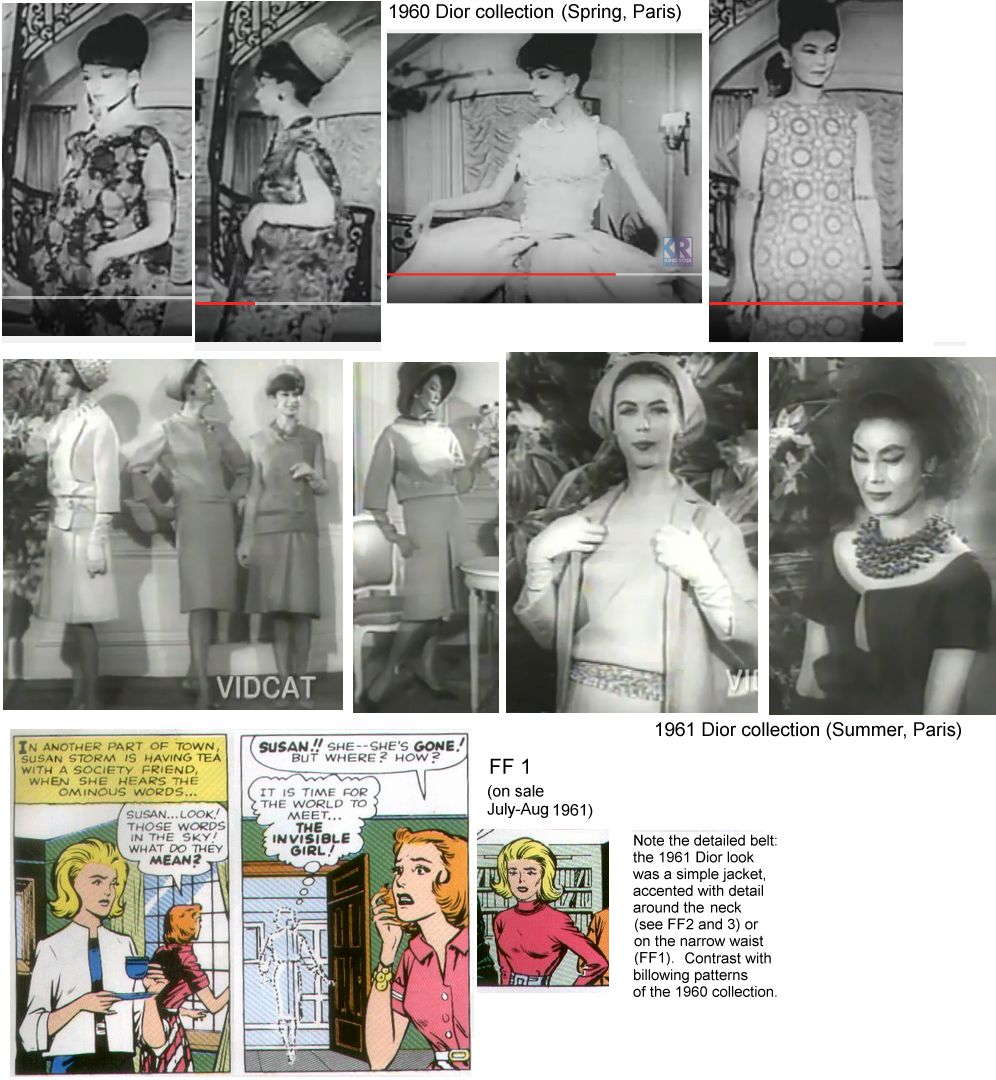

A close look at issue 1 shows that Sue's fashion sense reflects the Dior collection from 1961, which is very different from the previous year's style. Dior was the hottest fashion house at the time: Dior himself had just died in 1957, replaced by Yves Saint Laurent, who was himself then replaced by Marc Bohan for 1961. Elizabeth Taylor bought twelve of their dresses from this collection. Contrast the big flowery dresses of 1960 with the simple jacket and shirt from 1961. Sue Storm's fashion was up to the minute.

We tend to think of Reed as either a "do anything" scientist (not true),

or a man who designs rockets. But the comics reveal that his real

expertise is in high energy sources: see FF 13, 37, 38, 51, etc. While

the origin story is about his involvement in a rocket ship, the Mole Man

story shows that he also involved in the atomic bomb program. Look

carefully at the machine and how it works, and note that Reed already

knows a little about Monster Isle

Machines like that existed in 1961:

"The Soviets, who had been calling for a test ban since the mid-1950s, took a major initiative in early 1958 when they called for an American-British-Soviet test moratorium. [...] The experts concluded that a network of 170 control posts in and around Eurasia and North America would be able to detect atmospheric tests down to one kiloton and 90 percent of underground tests down to five kilotons." ( emphasis added: source)

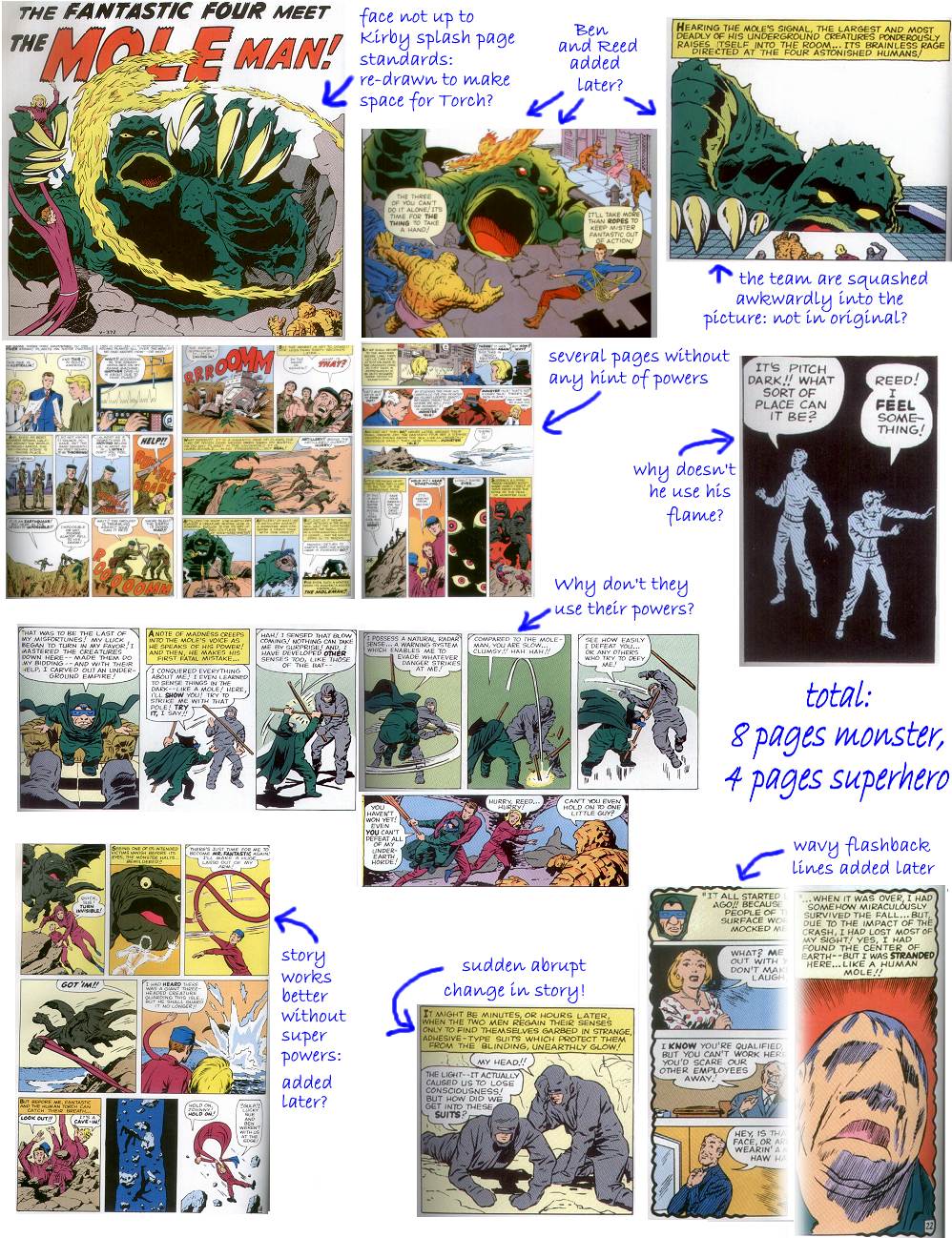

So Reed had access to those control posts, with their machines for detecting and triangulating tremors around the world. So Reed represents both of the great and powerful discoveries of the cold war: space travel and the atomic bomb.Mark Andrew makes an argument that I find compelling: FF issue 1 was two new stories added to an existing (unused) monster comic story.

Here is his evidence, plus some of my own:

The conclusion is obvious: when they designed FF1, Lee saved some time: the intro is new, the origin is new, and he got Jack to adapt an existing 8 page monster story into a 12 page first adventure.

Add up the pages: 8 pages for the intro, 5 pages for the origin plus 4 pages added to the monster story, and the original 8 page monster story: Stan got a 3 story book by taking 1 old story and adding 2 more.

This isn't proof, but I find it compelling.