by “Tuk”

version 3.0

The first cover: the history of Marvel 10

The inside cover: a reputable company? 19

Page 1: Signatures, and dialog versus art 22

Page 4: Who wrote the monster pages? 44

Page 5: Why Lee was good at connecting with readers 50

Page 9: Heroes with moral flaws 67

Page 10: Who had the idea for superpowers? 76

Page 11: Was Lee “concentrating”? 80

Page 12: Heroes who fight each other 83

Page 14: The book was changed. Why? 93

Page 15: Lee did not understand the story 102

Page 17: Kirby was ahead of his time 112

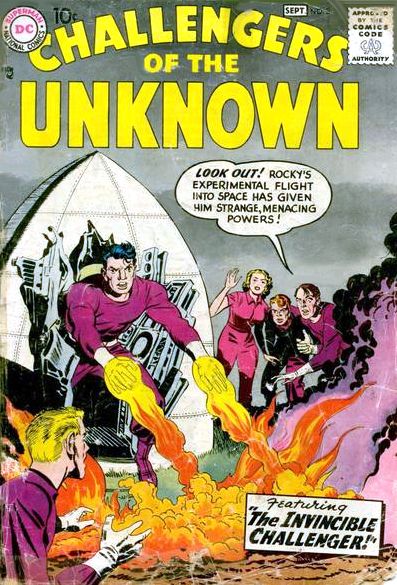

Page 18: A Challengers story, no superpowers 115

Page 19: Another smoking gun 118

Page 20: The emotional core 125

Page 21: forgetting the name of the villain 132

Page 22: The dialogue weakens the story 135

Page 23: Removing humanity from the story 139

Page 24: Powers added later 142

Page 25: Where’s the humour? 147

Who wrote the other Fantastic Four stories? 158

Who wrote the other Marvel stories? 179

Appendices

1: Kirby the writer, pre 1961 218

2: Lee's version of events 230

6: Kirby’s career in brief 261

7: How the Challengers became the Fantastic Four 264

9: Reconstructing the original book 284

10: How Lee’s claim evolved 296

About the author 301

In this book I examine Fantastic Four issue 1, to see how the Marvel Universe was created.

I argue that the creation process was like the creation of the painting The Last Supper. One man (Leonardo da Vinci) created the painting, and another man (the owner of the building) made changes. Some people liked the changes, and others did not. Are the changes enough to say that both men are co-creators of The Last Supper?

Here is The Last Supper. Below it is the closest we can get to the original.[1]

Note the changes.The “real” Last Supper is faded and cracked, and has a doorway cut through it. These change are due to decisions made by the owner of the building. The owner wanted the painting to be permanently on the wall of the convent dining room, so it got faded and cracked. And the owner (or his successor) decided to add a door through the wall.

These changes made the painting better for the core audience, the nuns who were eating dinner. They liked that the painting was always there, even though it meant it became faded. The fading added to its character. And they liked the new doorway, it meant they could go about their business more easily. And what else was the painting for, except to inspire them to do their holy work? So the changes added real value, at least for its original market.

However, later art critics felt that the loss of da Vinci’s vibrant colours, and the missing doorway section, meant the owners actually damaged the painting. So the owners do not qualify as “co-creators” of the painting. Even though the nuns liked the improvements.

I argue that Jack Kirby was like Leonardo da Vinci, and Stan Lee was like the building owners. Kirby created a rich and powerful story, and Lee then changed it. Some people feel like Lee’s changes made the story better, by making it more accessible. Others think he made it worse.

To measure Lee’s overall contribution I compare sales of the Fantastic Four to sales of Kirby comics before and after he worked for Lee. And I show that Lee’s net contribution to sales was probably zero.[2]

And so I argue that Kirby, like Leonardo, was the sole creator of his work, even though his boss made changes that some people like. Because, judged by sales, Lee added no value at all.

In this book the Marvel Universe refers to the foundational characters: the Fantastic Four (first appearance 1961), the Hulk (1962), Spider-man (1962), Thor (1962), Iron Man (1963), Dr Strange (1963), the X-men (1963) and the Avengers (1963). In this book I argue that Jack Kirby created these characters[3], and Lee’s merely simplified his stories

Most of this book is a detailed examination of Fantastic Four 1, the book that started it all. It is the primary source document and therefore our best guide to who did what. It contains three stories: the introduction, the origin, and the Mole Man story.

The first story (8 pages plus cover) is titled “The Fantastic Four”. A mystery man fires a flare gun and the words “Fantastic Four” appear in the sky. Three other people then stop what they are doing and gather to the call.

A high class woman is having tea with a friend. She sees the message, turns invisible and catches a taxi. A monstrous man is trying to buy clothes to fit. He sees the message, angrily breaks through the door and his appearance causes people to panic. Finally, a teenage boy is fixing a car with a friend. He sees the message, turns to flame, and flies off. The air force think he is some kind of enemy missile, and attack him. He barely escapes and the four of them are now together.

The second story (5 pages) has no title. It tells the origin of the group’s powers.

They have an argument then sneak into a rocket launch site. They take a rocket into space but are hit by cosmic rays. They crash land the rocket, and find they each have strange powers. They decided to work together.

The third story (12 pages) is in two parts. Part 1 (6 pages) is called “The fantastic Four Meet The Mole Man!”

Seismograph readings detect underground tremors. A giant monster is tunneling underneath nuclear power plants and they then disappear into holes in the ground. The team trace the origin of the tremors to a remote island. They visit the island and find it guarded by a three headed monster. The ground then caves in and two of them find themselves in a dark cave. Then they see a blinding light that causes them to collapse. They wake up wearing radiation suits, see a valley of glowing diamonds, and meet The Mole Man.

Part 2 (6 pages) is called “The Mole Man’s Secret!”

On the island, the Thing battles another monster. Back underground, we learn how the Mole Man found the underground caves and went blind. He tries to show his skill in fighting. Then the Thing and the Invisible Girl appears. The Mole Man summons his monsters, and the team runs away. As they fly away in their plane the island explodes.

Analysis shows that the Mole Man story originally featured different characters with no superpowers. That is, it was an unrelated story originally intended for one of Marvel’s monster comics. This and other evidence indicates that the origin story was originally planned in the same way as Spider-Man, Ant-man, Thor and Iron Man: as just one of several stories in a monster or sci-fi anthology comic.

The choice to instead make it a new comic must have been a last minute decision: else why waste time changing an existing story? The Mole Man story could have been unchanged, been used in another comic, and a new, more appropriate Fantastic Four story created instead.

Now we come to who created the stories. By comparing Lee’s dialog with Kirby’s art we can see different levels of:

Based on this, we can infer how the Fantastic Four was created:[7]

Lee had a high opinion of his own contribution (making suggestions and writing the final dialog), so after the first year[11] he began to call himself the writer. He was thrilled to see the amount of fan mail, so he began to relax and add wisecracks and asides. The story was entirely contained in the art, so Lee had plenty of space to have fun without worrying about the plot.

The bottom line is that Kirby created, and Lee simplified. Lee’s changes shifted the audience demographic slightly (to younger readers) but did not affect total sales figures.

Now let us examine Fantastic Four issue 1 in detail.

The cover to Fantastic Four issue 1 tells us the history of Marvel comics. Where? In the details and small print, the parts that most people ignore.

Let’s start with the price, as this is the background for everything that follows.

Comics had been ten cents for decades, despite inflation. This made them less and less profitable. Publishers were scared to raise the price in case young readers just went to a competitor instead. So instead they cut costs, offering fewer and fewer pages.

But the comics still took up space in stores. Almost anything else in that space would have made more money for the retailer. So ten years later most stores were replacing comics with more profitable magazines. But even here in 1961 everyone knew the writing was on the wall. Comics were barely profitable, and publishers knew it. The biggest sellers, like Superman, or Disney’s Uncle Scrooge, could make up for small margins in high volumes, nearly a million copies per issue. But comics like the Fantastic Four were not expected to sell more than 180,000 copies per issue. The publisher, Martin Goodman, focused nearly all his attention on his men’s magazines instead.

Look at the box on the right that says “Approved by the Comics Code Authority”. What does that tell us? Everything!

In 1954 psychologist Fredric Wertham published the book “Seduction of the Innocent”. This created a moral panic against comics as a bad influence on children. Distributors and stores stopped handling as many comics. There were calls for comics to be banned. The industry was in crisis. As a result the comics companies set up the Comics Code, to say “we are safe and inoffensive now!” The code banned anything that might offend people, and enabled some comics to keep publishing.

The bottom line is that, since 1954, publishers were afraid to publish anything that might take risks or be adult in nature. Comics became bland. The most admired comics publisher of the time, EC, simply stopped publishing comics. In short, comics were in a bad way.

The next detail I want to point out is “IND”, short for “Independent News”, the company that delivered the comics to retailers. These three letters speak volumes.

In 1956, Goodman relied on the American News Company for distribution. But in 1952 the government began investigating it for anti-competitive practices. This made other publishers nervous, and they gradually stopped using the company. In June 1957 the American News Company ceased trading, leaving Goodman with no way to get his comics into the shops. In one month he had to cancel eighty titles[12].

Thanks to the Wertham moral panic, and the very low profit margins from comics, most distributors were not interested in taking on Goodman’s titles. Desperate, Goodman finally turned to his main competitor for help: Independent News was the distributor owned by National Periodical Publications, the company better known as DC, publisher of Superman.

Independent News said yes, they would distribute their competitor’s comics, but not the eighty plus titles Goodman was publishing. They would only distribute eight titles per month. So Goodman fired all of his writers and artists, except for one man: his nephew (by marriage), Stan Lee. Lee now had to organise everything himself, hiring freelance comic creators as needed. Lee feared for his own job. Artist DIck Ayers recalled:

Things started to get really bad in 1958. One day when I went in Stan looked at me and said, “Gee whiz, my uncle goes by and he doesn’t even say hello to me.” He meant Martin Goodman [owner of the company]. And he proceeds to tell me, “You know, it’s like a sinking ship and we’re the rats, and we’ve got to get off.”[13]

Now let’s look at that other symbol, “MC”, meaning Marvel Comics. In previous years, Goodman’s comics were branded as “Timely” or “Atlas”, and since Spring of 1957 they had no shared brand at all. So why was the cover stamped MC?

“Marvel Comics Group” was just a term used for selling advertising space. The Marvel Comics group was the group of similar comics that all had the same adverts. Women’s magazines would have a different group name, men’s magazines had a different group, sports magazines had a different group, and so on. This matters for two reasons.

The book “The Secret History of Marvel Comics” gives more details of Goodman’s attitude to content: to pay as little as possible for it. Content was the least important part of his business.

Fantastic Four 1 is cover dated November 1961. The comic was on sale in August 8 and created in April. There was something very special about April 1961: Kirby was back!

Kirby's decade was a story of dizzying highs and devastating lows. He was one half of the Simon and Kirby Studio, a birthplace of new ideas, new genres, and hit titles that had at times sold over a million copies per issue.[15] Simon and Kirby were the superstars of the business, and their names appeared on covers.

In 1954, they launched Mainline Publications, their own self-publishing venture. In a case of spectacularly bad timing, Wertham's campaign against comic books took down the distributor they shared with EC Comics, resulting in Mainline's insolvency.[16] By early 1956, the Mainline experiment was over.[Footnote: Robert Lee Beerbohm, "The Mainline Comics Story: An Initial Examination," Jack Kirby Collector 25, August 1999.]

Switching from owner back to freelancer, Kirby continued producing stories for the Prize romance books, sold stories to Stan Lee at Atlas, to Harvey where Simon was editor, and his work appeared in Charlton comics in the form of Mainline inventory. The industry continued to shrink, and by the latter half of the decade Kirby was trying to diversify into the more lucrative world of newspaper strips, producing a number of samples. While he continued with monthly comics to pay the bills, his dream was elsewhere. In 1957, Kirby landed on his feet at DC where the pay was good. He successfully pitched the S&K concept, Challengers of the Unknown, and was welcomed back without Simon.

In 1958, Kirby realised his dream of a newspaper strip, Sky Masters. Unfortunately, his editor at DC, Jack Schiff, had arranged the contact with the newspaper syndicate, and was due a portion of the proceeds. Kirby believed that his future assignments at DC were being leveraged to increase the editor's take from Kirby's share, from which he was already responsible for paying the inker. When the two wound up in court, Schiff won the judgment: Kirby was blacklisted at DC, but his work on Sky Masters continued for another year.[17] His DC earnings had run dry by early 1959, but Kirby had already picked up assignments from Archie, Western, Prize, Gilberton,[18] and back at Atlas, from Stan Lee.[19] By early 1961, Atlas was Kirby's sole source of income. The pay rates were half what DC had paid: he really needed the money, yet he could see that Goodman’s comic divison might shut down at any moment. More than ever, Kirby had to create new hit comics, and fast!

Research suggests that writers hit their creative peak at age 42[20], and artists at 48[21]. Kirby was 43. Just using the facts available to us in early 1961, we know that Jack Kirby, America’s number one comics creator, was about to do something world changing.

Lee later claimed that the Fantastic Four was all his idea, and that he was inspired by the Justice League comic. That claim does not stand up to examination: appendix 2 has the full details.

Based on that claim, some people like to see a slight resemblance between the cover of Fantastic Four issue 1 and the cover of The Brave and The Bold 28 (the first appearance of the Justice League). However, there is a much closer resemblance to Kirby’s monster comics:

(See for example Journey into Mystery 58, or Amazing Adventures 5, published the month before Fantastic Four 1).

We will see this again and again in the origin of Marvel comics: everything can be traced to Kirby’s earlier work.

All sides agree that the final text in this comic was written by Stan Lee. Let’s look at that text. Reading left to right, the first text we see (other than the title and small print) is the Invisible Girl:

“I can’t turn invisible fast enough!”

This is not true of course. On page 18 she can turn invisible instantly when a monster is chasing her. But this is not necessarily a lie, it’s just a character’s opinion in the heat of the moment. And maybe it’s just part of the symbolic cover: symbolic covers were normal for the time.[22]

The truth or otherwise of Sue’s statement is a silly, trivial detail. But it raises a very serious question: how far can we go before “not exactly true” becomes a lie? Look at the next statement on the cover. This is in a text box, so it’s the editor speaking to the reader:

FEATURING “THE THING!” “MR. FANTASTIC!” “HUMAN TORCH!” “INVISIBLE GIRL!” TOGETHER FOR THE FIRST TIME IN ONE MIGHTY MAGAZINE!

The editor implies that we should recognise these names. He implies that they have appeared somewhere before. But neither claim is true. A different character called “The Human Torch” once had his own comic, but if you bought this comic expecting that character you would be cheated. You would find you have been tricked into buying somebody completely different.

So this is a false claim, about the real world, made with the intention of getting your money. But is it a lie? How far can an editor allow the bending of the truth in order to get money? Turn the page and we will see.

Look on the inside front cover below the advertisement for building muscles. This tells us much more about the business.

If you are following along an ordinary reprint it probably misses the ads. If you have the scans[23] you might notice that it has the wrong page, using the inside front cover from issue 8 instead of issue 1. But they are very similar: all the early Fantastic Four inside covers had the same small print. I want to draw attention to the official company name.

The officially named publisher of Fantastic Four 1 was not the real publisher, Martin Goodman’s Magazine Management. It was not Timely, or Atlas, the names used when talking to readers. It was not even Marvel Comics Group, the name use for advertisers. It was “Canam.” Why does this matter? Well, check the small print of other comics published by Magazine Management:

These companies do not exist. Or rather, they do not have significant assets like buildings and employees.[24] The technical term is “shell companies” (empty shells). There are legitimate reasons for shell companies[25], but they are very commonly used to prevent losing money if you are sued. Goodman was often sued, and violated FCC regulations on at least four occasions:

The modus operandi that Goodman adopted to satisfy his thirst for a quick profit at any cost (except, of course, for the cost of investing in quality original material) got him censured by the federal government on at least four occasions.

In addition, he was sued by employees and competitors and, like many of the low-rent pulp and magazine publishers that entered the comic book field in the 1930s, was forever labeled by freelancers and comic book historians as a swindler of creative talent.[26]

One way to cheat a writer was to pay them for a story once, then later to use the old story again with minor changes, and without paying the original writer again. The “Secret History of Marvel Comics” (by Bell and Vassallo) has examples of Goodman doing this. Lee seems to have followed the same practice. For example:

The first time Stan Lee worked with Jack Kirby on a story (TWO GUN KID #54) Lee actually gave Kirby a plot. The plot was taken from an old Timely Western story called "The Tenderfoot" (WILD WESTERN #50) which was not written by Lee. Lee later used the same plot again in RAWHIDE KID #36).[27]

Another way was to simply not acknowledge their work at all. In Lee’s 1947 book “Secrets of the Comics” Lee gives Goodman all the credit for the existence of Captain America, never mentioning the book’s creators, Simon and Kirby, at all.

Another indication of the company’s standards was the advertising it accepted. These ads were perfectly normal in the comics industry as a whole, but low standards across the industry are still low standards. While we are on the inside front cover, look at that advertisement for big muscles. Look closely at the picture: it seems to have a fake head posted on the body. Look at the promise: huge muscles in “ten minutes of fun each day”.

Let’s be clear: this advertisement is lying to us. And while we’re at it, look at the other ads in the comics. Some offer magic tricks of highly dubious quality. Another says “if you know just 20 people you can make at least $50, more likely $100 to $200 in your spare time”. This was a fortune in 1961 when a comic was just ten cents. Those numbers are all theoretically possible, but saying “at least” and “more likely” is simply a lie.

Nearly all the ads are like this, either very misleading or simply lying. For example there are two full page ads looking for artists. But the comic book art industry was shrinking, indicating an oversupply of artists, and artists were the bottom of the pecking order. These ads exist precisely because artists could make more money money from kids responding to these ads than from working in the industry.

All of this confirms what we saw in the small print: the business was not to be trusted.

We are about to begin the story itself. Let’s pause and consider where we are.

What happens next? How can the boss’s nephew make himself so important to the boss that he can never be fired? The answer is in the comic.

Now we get to the story itself. I will use the page numbers written on the bottom right hand corner of each page. So the splash page is page 1, and the final page of the Mole Man story is page 25.

Before discussing the signatures, let’s look at how the story begins with a yellow box with four circles and the four heroes. The dialog says these are the Fantastic Four. But haven’t we seen this design before somewhere? It was used on the original ad for Kirby’s Challengers of the Unknown.

This is the first of many indications that the Fantastic Four was simply a continuation of Kirby’s Challengers, with minor changes for legal reasons.[30]

At the top right we see the names “Stan Lee and Jack Kirby”.

What does it mean to have a name on a comic? Not much, according to Lee. Lee discussed names on comics in his 1947 book, “Secrets Behind the Comics”:

The man whose name is signed to a comic strip is not always the man who really writes and draws the strip. Then why are false names sometimes used? False names are sometimes used because a comic strip may have many artists! One artist may create a comic strip... the strip may grow so popular than the one artist who created it cannot draw all the strips needed. So, the editor hires another artist to draw the same strip. But the first artist wants his name on all the strips! So, even though the new artist draws some strips, the name of the first artist will appear on all of them! Remember: you cannot always tell who writes or draws a comic strip by looking at the name which is signed! it may be the wrong name or a fictitious name![31]

Lee was writing in 1947, so probably had in mind Bob Kane, who recently (1943) left Batman but his name still appeared on every issue. Unlike most creators of the time, Kane understood the legal power of a signature: Kane made himself irreplaceable by getting a contract where his signature had to appear on every issue of Batman, even when Kane had little or no input.

The largest section in “Secrets Behind The Comics” argues that Martin Goodman should take credit for Captain America. This was probably the motive for the book, as Siegel and Shuster had recently claimed credit for Superman. Goodman would not want Simon and Kirby claiming the rights to Captain America. So Lee promoted Goodman as the genius behind the strip:

In 1961 Lee was placed in the same predicament again. Here was Kirby, the creator of the company’s biggest hit, with his name on a new comic. Lee had to assert his claim over the Fantastic Four, just as Goodman had asserted his claim over Captain America.

Bosses often take credit for their employees’ work. This is not a controversial idea. In science this is called the Matthew Effect, after the statement in Matthew 25:29 that “to he that has shall be given”. If a scientific team discovers something it is generally the head of the team who gets the glory and the awards, regardless of who did what. The team head is then more likely to be the team head in future, and will therefore attract even more money and more awards regardless of who did the actual work.

As head of the comics division, Lee could put his name on any comic he wanted. He could call himself “writer” even if he was merely copywriter - someone who added the final printed copy (text) to another person’s ideas. Within the comics industry Lee had a reputation for signing his name on other people’s work, but perhaps that reputation was not deserved? In this book I focus on the primary documents to see where the evidence leads.

Lee did the same thing when he left writing comics in 1972, “Stan Lee presents” was written at the top of thousands of comics that Lee seldom read, let alone created.[32] True, Lee did not assert that he wrote these later comics, but he did not assert that he wrote Fantastic Four issues 1-8 either. We’ll discuss that next.

For the first year, the books were merely signed “Lee and Kirby”

Lee did not call himself the “writer” until issue 9, dated December 1962[33]. For the evolution of Lee’s claim to be the writer see appendix 10.

“Lee and Kirby” is like “Simon and Kirby”, where both men shared in writing and drawing (though Simon also had to split his time with running the company).

Fantastic Four 1 was essentially a Goodman monster comic. Goodman monster comics were signed “Kirby and X” (where X is usually the inker Dick Ayers, but could be Joe Sinnott, etc).

This topic is discussed in more detail when we examine page 4. That analysis suggests that “Kirby and Ayers” meant the same as “Simon and Kirby”: it meant that between them they created the comic. No more, no less. If it meant “A wrote it, and B drew it” then it would have said so.

Give that “Lee and Kirby” just meant “both were involved”, and given that Fantastic Four 1 was essentially a monster comic, and given that Kirby wrote the monster comics, the signatures “Lee and Kirby” would suggest that Kirby had at least some part in writing Fantastic Four issue 1.

For how Lee’s claim to be the writer evolved, see appendix 10.

However, the finished dialog, written onto Kirby’s finished pencils, was by Lee. Nobody disputes that. That is what allows us to compare Lee’s dialog with Kirby’s art, and see what that tells us about the creation process.

Now we begin the story itself.

The dialogue refers to a fictional "Central City". Here are some real life locations called “central city”: There’s Central City, Missouri, Central City, Nebraska, Central City, Colorado… notice anything in common?

City planners call a place “central city” because it’s central. The clue is in the name.

But a few pages later we see that this comic book city is on the coast, the opposite of being central.

It’s a minor point, but it suggests that either Lee did not know what would happen later, or he didn’t care. We will see this again and again as the book continues: either Lee did not know what was in the book or he did not care.

The art shows that this could easily be New York, where Kirby and Lee both lived. But for the first two issues Lee called it Central City. In issue 3 Kirby set a battle outside the Bijou Theatre, a landmark on New York’s 45th street[34], and from then on Lee began to refer to the city as New York.

This is a common theme throughout the book: Kirby’s art shows things that might exist in the real world, then Lee’s dialog destroys the believability. This matters because many fans felt that realism, such as heroes living in New York, was the key to Marvel’s success:

It was important that Lee's heroes lived in the real world, and not in Gotham City or Metropolis, because they were real people. That is, Marvel Comics imagined how real people might act if they suddenly gained superpowers -- confused, conflicted and not necessarily eager for the responsibility. They were a departure from that straight-arrow hero of the Golden Age, Superman. The next age belonged to Marvel. And Stan Lee ushered it in with his creations.[35]

Calling the city “Central City” contradicts Lee’s later claim that having superheroes “live in the real world” was his own idea from the start:

"For years we had been producing comics for kids, because they were supposed to be the market," Lee explained. "One day, out of sheer boredom, we said let's do something we would like. So we tried to get rid of the old clichés. Comics were too predictable. Why not accept the premise that the superhero has his superpower, and then keep everything else as realistic as possible? If I were Spiderman, for example, wouldn't I still have romantic problems, financial problems, sinus attacks and fits of insecurity? Wouldn't I be a little embarrassed about appearing in public in a costume? We decided to let our superheroes live in the real world." [36]

Realism was not a minor thing, Lee said being “in the real world” was “the whole formula” for their success:

"The whole formula, if there was one, I think was to say -- let's assume that somebody really could walk on walls like Spider-Man, or turn green and become a monster like The Hulk, that's a given, we'll accept that, but accepting that -- what would that person be like in the real world if he really existed? Wouldn't he still have to worry about making a living, or people distrusting him, or having acne and dandruff, or his girlfriend jilting him, or what are the real problems people would have? and I think that's what made the books popular -- but it took years for the competition to realize that, I'm very happy to say."[37]

We will see throughout issue 1 that the realism, the secret of Marvel’s success, came from Kirby, and Lee fought against it.

The art shows wobbly writing projected onto clouds. That is, something like Batman’s Bat signal, or (a couple of years later) Spider-Man’s Spider Signal. The pulp hero The Phantom had a similar device.

Sky projection is a real thing, and has been used since the 1920s as an advertising gimmick. Modern laser projectors make it even easier and the words are surprisingly clear (due to the distance and therefore viewing angle)

This works with regular lights, but the first laser had just been built, the year before Fantastic Four 1 came out, so Kirby may have had this in mind.[38]

It is possible of course that the story involves radically new technology that appears to defy all known laws: the text says the words “take form, as if by magic” and then later form into the number 4. That would require numerous new discoveries and technologies that are not implied by the story. If we allow things that are not implied then why not say the Fantastic Four are really fluffy bunny rabbits in disguise, and are controlled by a flying teapot just out of view? Occam’s razor is the principal that we should shave off unnecessary parts from any theory. New flare gun technology is not necessary, so we should shave it off.

Other “problems” with the image are easily explained: the wobbly edges to the letters are the same as we see in the sky projection photos. And the smoke appearing to come from behind the building is a mistake in the reprint: the original published comic shows it could have been from either in front or behind - the point is that the people watching do not know its source.

In conclusion, just as with the New York / Central City example, the art shows something that could be real. But the dialog (and the reprint) makes it not real.

Reed’s first words are:

It is the first time I have found it necessary to give the signal! I pray it will be the last!

This suggests he does not want to use his powers to help the world. But later pages reveal that he hijacked a rocket ship, taking enormous risks to oppose the authorities, and did not hesitate in using his later powers aggressively. Then the Mole Man story shows him piloting his own plane, so there’s a lot of planning. The later dialog says Reed called himself “Mister Fantastic”. Is this a hesitant man? A man who prays he will never have to use his power?

So is Lee unaware of what happens later in the story? Or is Lee just careless? Or not at all concerned with internal contradictions? The following pages support all three conclusions.

At the end of page one we already have hints that Lee is adding dialog to a story he has never seen before, that Lee contradicts himself, and that above all the the original story was realistic but Lee makes it unrealistic. This evidence will mount up, page after page.

The first person we see in action is Sue Storm. She is also the first person we saw on the cover (reading left to right, top to bottom), and will be the first person to gain powers. Her face is confident and serious. She learns of the alarm and does not hesitate, even to check for herself, or to tell her friend, but she immediately moves into action. She pushes men (and some women) out of the way.

Also note that outfit. Later issues of the comic mention Dior several times (most notably in annual 1). Let us compare the Dior summer 1960 collection (beehive hair, big flower prints dresses) to the summer 1961 collection: the latest fashions are exactly what Sue is wearing: minimalist jacket, three quarter length sleeves, accented with neck details.

Why does this matter? The old vision of women, as pretty things wearing long flowery dresses and impractical hair, changed in 1961. The future belonged to practical women who got things done. We are now building up an image of Jack Kirby from his art. He’s a guy who noticed what was up to date and looked to the future. Later we’ll see examples of Kirby being up to date with politics and science as well.

The art puts Sue first: First on the cover, first to use her powers in the book, first to use her powers after the spaceflight, and she is the one to make Ben join so the flight can go ahead. She acts decisively without hesitation, and pushes men out of the way. Later art and later issues will make this even clearer.

We saw the same thing with Kirby’s Challengers, even though they were originally just men. (June, the computer expert, joined the group later.) The origin story began with the men coming second to four heroic women.

Now that we have seen how Sue as described in the art, let’s look at the dialog and see the contrast:

So it has happened at last! I must be true to my vow! It is time for the world to meet The Invisible Girl!

It’s subtle, but it’s a different message. According to the dialog, Sue was waiting for someone else to tell her to use her powers. That other person was of course a man. She was apparently hesitant and only did it because of her vow: a vow she made to men.

On its own this is a minor point. But examples in later Fantastic Four comics, are far, far worse. The art often showed her as independent and dominating men, and on the same panels Lee added dialog that made her scared or subservient to men.

Once Kirby left and Lee wrote the book (issues 103-125), Sue was reduced to fainting and being rescued almost every issue.

While the boys were out fighting bad guys, Lee’s Sue sometimes stayed home to answer the phone.

The result of Lee’s dialog (and later his writing) is that readers now see the early Sue in that context. For example, a reader recently criticised page 2 of Fantastic Four issue 1 for showing Sue “demurely drinking tea”. Would the same critic have referred to James Bond in the same pose as “demurely drinking Martini”?

In short, Kirby’s art empowered women, but Lee’s dialog made them weak and dependent on men.

Strong, independent women are generally considered a sign of good writing. Or at least modern writing.

The remainder of the dialog on page 2 simply describes what we can already see in the art. Jerry Bails, founder of Alter Ego, described this problem a couple of years later:

Stan writes a one page synopsis of an entire FF story [after meeting with Kirby: see appendix 4] then Kirby breaks down the whole story even before any dialogue or captions are written. Naturally then, there can be little in the way of real plot carried in the "script". Captions must be limited largely to describing the action in the box, and dialogue must consist largely of wisecracks, both of which can be added directly to the pencilled drawing.[39]

In this first issue the problem is even worse: Lee is using the dialog as well as the captions to describe what the reader can already see. Later he will adopt the method observed by Bails, leaving dialog free for wisecracks. Either way, in these pages the story is fully told in the art, and Lee’s dialog is redundant.

“Show, don’t tell” is the usual advice when writing. So in this as well as the sexism, Kirby is shown as a better writer than Lee.

We saw on page 1 that Lee might not know what happens on later pages. We see it again here on page 2. A taxi ride is a classic example of a time when a writer can develop the plot: a taxi ride means they are going to somewhere, but the hero has time to anticipate what will happen. So this is a perfect moment to reveal information, foreshadow what is to come, and build the tension. But instead Lee simply describes the taxi ride. He has the taxi simply wander aimlessly, killing any sense of urgency, whereas the art shows it speeding, leaving a trail of dust in its path.

The speeding taxi makes a far better story, but it requires some idea of what is happening next.

Lee’s taxi dialog suggests again that either he is a bad writer (killing the tension) or that he does not know what happens next, and is just making up dialogue to fit whatever he sees for the first time when seeing each page.

Lee’s apparent method, taking a fully complete story and adding his own comments, evolved over time into something unique and appealing to many fans (while irritating and empty to others). It’s like Mystery Science Theatre, where a clever friend is watching the story with you. The fact that the story does not actually need dialog gave him plenty of space to chat with the reader, add wisecracks and asides, and so on. Competitors like DC comics did not have that luxury. Kirby could tell a complete story just with the art, but few other creators had that skill.[a]

IMHO, Lee's comics do in fact read better, in the main, than their DC counterparts, despite Lee's writing being perhaps technically worse than the DC writers. The fact that Lee is actually NOT the writer, but is a kind of a disreputable uncle figure improvising commentary on, and even undermining, a story he has little personal investment in, made these comics feel livelier to me as a kid.[...] Neither one is very readable to me now, but to the young me the Marvel books felt spontaneous compared to the neatly scripted DC superhero books.[40]

On this page we start to see Ben’s dialog:

Bah! Everywhere it is the same!

Bah! I cannot delay!

Bah! What'd you expect?

Bah! How can you care for that weakling when I'm here?

Notice a pattern? Ben doesn’t have much dialog in this issue (he appears to have been added as an afterthought to the Mole Man story, but we’ll get to that) so all this “bah”ing stands out. It’s fairly typical of the clunky dialog in this issue.

It is commonly claimed that Lee improved Kirby’s dialog. But the evidence from the comics themselves shows the opposite. It is true that in later years kirby preferred a richer, more intense style. By 1970 he had spent thirty years writing simple dialog and human level plots, and he had nothing to prove. He wanted to move on to bigger topics, and they required bigger language. But in 1961 Kirby was still writing simple language that any child could follow. I give examples in appendix 1.

Compare Kirby’s dialog in appendix 1 with Lee’s dialog in Fantastic Four 1. Is any of Kirby’s dialog hard to follow? Would any of it feel “clunky” to a child? Does Kirby lack the human touch? Judge for yourself.

Both Kirby and Lee could write easy dialog. But compare their dialog, and ask yourself, who was the better writer?

Lee’s job at the time was to keep the comics simple.

[O]ne edict that my publisher had was that the stories had to be geared towards young readers; or unintelligent older readers. We weren't supposed to use words of more than two syllables, and we had to have simple plots; no continuing stories, because he felt our readers weren't smart enough to remember from month to month where they had left off. It was really boring. [41]

This seems to be exactly what he was doing in Fantastic Four issue 1: Kirby provided a complex story and Lee simplified it for younger readers.

So far we see energy in the story, and interesting plotting. But it’s all in Kirby’s art, not in Lee’s dialog. Perhaps we could still argue that Lee wrote the original plot, but let’s look at the next page.

This page features a lumpy orange monster, then half under water, then bursting from underground. These are typical scenes from numerous Kirby monster stories.[42] So whoever wrote those scenes probably wrote these Fantastic Four scenes as well.

The Kirby monster stories are all conveniently reprinted in the “Monsterbus”. If we examine each one we find that Stan Lee did not sign a single one. But many of the monster comics have the signatures “Kirby & Ayers” and once “Kirby & Sinnott”.[43]

Lee (or someone working for him) would often paint over their signatures. Here’s an original penciled monster page: you can see where the signatures were covered up.:

Ayers later wrote

So… regarding those Kirby / Ayers signatures… I always put the signatures on our work together just as I always sign my work. I noticed that the ‘whiteouts’ were happening and it sure didn’t make me happy for I usually had the signature as part of the composition of the drawing. It was a sore point. I’m not keen on the credit boxes that are added to the drawing and confuse the composition of my drawing.[44]

In later years, reprints with signatures were altered to say that Kirby and Ayers only did the art. In this example the scan is poor, and the colouring makes it hard to see in the original, but you can just about make out how the rock has been extended to make space for the changed credits:

It seems unlikely that Lee had written these stories, as his signature was never there. After Marvel’s bankruptcy in 1996-97, the question of legal ownership became a hot topic. At that point Lee began to say that he, or possibly his brother, wrote them.[45]

But there is no actual evidence (beyond those late claims) for Lee or Lieber writing them:

In summary, page 4 reminds us that the Fantastic Four was in many ways a monster comic, and Jack Kirby wrote all his monster comics himself.

A couple of months before this issue was written, Kirby had just finished plotting “Sky Masters”, a newspaper strip about the space race.

The Sunday edition would include a section where Kirby covered real world space science.

Kirby’s superhero and romance comics strips will be discussed on a later page. The point is that Kirby was already producing high quality material in every area touched on by the Fantastic Four: superhero, sci-fi, monster, emotional drama, etc.

The Fantastic Four is not some great leap forward, or some miracle that can only be explained by Lee adding some mystery ingredient. The Fantastic Four is just Kirby doing what Kirby always did. If anything, the Fantastic Four is Kirby when he’s rushed, because he worked on five other books the same month. It’s a normal Kirby comic, no more no less, except the dialog got dumbed down.

As mentioned earlier, Lee writes as if he is sitting next to the reader, commenting on a story that somebody else has written. Page five has a particularly clear example:

(Dialogue:) But what does it add up to, chief? What?”

(Caption box:) What does it add up to, indeed? Perhaps if the police officers could witness still another scene in a local service station, they would find yet another clue – as will WE!

Why was Lee so good at acting like the reader, not the writer? Other writers sounded fake when they wrote that way. The simplest explanation is that Lee was not faking: he really was reading the story, and reacting like any reader would react.

A comment like “what will happen next?” is only possible because there is space: normally the story would need that space for some useful information. But all the information in this story - the entire plot - can be seen in the art. So whoever wrote this story thought in terms of pictures, not words.

Later on the page we see that Johnny Storm loves cars.[46] This story comes soon after the

opening of America’s interstate highways (the act was passed in 1956). That and increasing wealth meant cars became a big part of youth culture.

This of course is just one data point, but it’s part of a pattern: this is a story based in the real world. This matters, because the art was as realistic as possible, but the dialog was not. And as we saw earlier, realism is what made people buy the book.

On this page we see Johnny turn to flame for the first time. Look at every time the Torch is on fire in this issue (and the next): he has no face, no legs, and does not use the "arm" shapes for anything. he is basically a continuous long flame with vaguely arm and head shaped flames. He is just as misshapen and monstrous as Ben, probably far more so.

This flame monster is a force of chaos, creating uncontrollable destruction wherever he is (without using his arms): destroying airplanes with men inside, setting fire to the forest, and making caves collapse.

In contrast, The Human Torch was a well known superhero owned by Goodman's company. He had a distinctive look, recognisably very human, and used his flame in skillful, human ways.

Lee wrote the dialog and called this new creation The Human Torch. Whoever decided the name, Lee seemed happy with it. And two issues later this new Torch was drawn to look like the original Torch. The art change was probably requested by Lee: Kirby had chosen a different style, more in keeping with the monstrous look of the others, and the new style took longer to draw.

Lee had previously shown himself keen to keep the look of the original Torch. When that Torch was relaunched seven years previously (1954), and the artist drew him slightly differently, the Torch art had to be changed by Carl Burgos, the original Torch artist. Lee was in charge of the comics, so the decision was probably his.

So the Torch we see is not the Torch Lee would have written, but a different, less controlled, more monstrous character.

Of course, the difference can easily be explained by Lee being creative. Perhaps he liked the idea of someone less controlled, more likely to destroy planes and set fire to forests? But the dialog does not mention this, and Lee usually mentions everything that matters. The only dialog that might hints that the Torch might be uncontrolled is when he says he warned the planes. But being able to warn the planes suggests at least some level of control.

While it is certainly possible, in theory, that Lee could have requested the new character in this uncontrolled form and then changed his mind, there is a much simpler explanation: Kirby had a long history of creating superhero stories, monster stories and horror stories. This monstrous, destructive fire being is just what we would expect from Kirby.

One year before this, Kirby created the fire creature Dragoom (Strange Tales 76). A couple of years before that, in Tales of the Unexpected 22, Kirby created flaming lava men (and did so again later in Thor). Around the same time, in Challengers of the Unknown, Kirby created a flaming monster (Showcase issue 12) and later a human figure with flaming powers (Challengers issue 6). Kirby’s best known fire demon was probably Surtur in Thor. Fire demons were Kirby’s bread and butter.

In later years Kirby said he threw in Carl Burgos’ Human Torch “for entertainment value”, but the context indicates this was an afterthought.[47] This is consistent with deciding on a flaming character first, then later thinking “we can get extra sales by making the link.”

So while it is possible that either Lee or Kirby created this Human Torch, the evidence suggests it is more likely to be Kirby.

It might be argued that Lee improved the character by his change in issue 3, but we can't say that without seeing what the more monstrous Torch would have worked out. The monstrous Ben worked well, so perhaps this would have strengthened the rivalry with Johnny. The question of whether Lee's changes add to sales figures is examined later.

Regardless of what happened in later issues, this part of the book is just about who created the ideas for Fantastic Four issue 1. And this page, like every other, points more to Kirby than to Lee.

Page seven has Johnny and a heat seeking missile. Not just any heat seeking missile, but the granddaddy of them all, the AIM-9 Sidewinder.[48]

The Sidewinder was the first big heat seeking missile, first used in 1958 to devastating effect.

The Soviets, weapons suppliers to half the world, later admitted that the Sidewinder’s near-biological intelligence was a complete revelation to them.[49]

This is an example of how Kirby’s art was often based on recent science and technology. But not just the art: the story was also based on the science: the Sidewinder was notable for being a heat seeker, with “near biological intelligence” for changing direction to follow a target. So what is more natural than that a flaming man should attract such a response, resulting in almost certain death for the hero?

This was a realistic response from the authorities: this was 1961, the height of the cold war, and the authorities saw what seemed to be a missile over the city. It kept changing direction, so what could they do except scramble military jets with Sidewinders?

However, this is where it become unrealistic. The art shows realism, but the dialog says the missiles carry a nuclear weapon.

Lee seems unaware that these are Sidewinders: why not use such a cool name if he knew it? Worse, not only did sidewinders not carry nuclear warheads, but using a nuclear weapon over one of your larger cities (probably New York, though Lee calls it Central City) would be madness.

So this is another example of Kirby’s art creating a realistic story, and Lee’s dialog making it unrealistic.

Readers my wonder why I keep discussing realism. Realism is relevant to the question of “who created what”, in four ways.

Although The Fantastic Four is conventionally called a superhero comic (or possible a monster comic) it is more accurately hard science fiction. Kirby described it as a look at what might be possible from radiation. Everything else is as accurate as possible.

The idea for the F.F. was my idea. My own anger against radiation. Radiation was the big subject at that time, because we still don’t know what radiation can do to people.[50]

"My stories were true. They involved living people, and they involved myself. They involved whatever I knew. I never lied to my readers. [...] If you analyze them, you'll find that I'm not really fictionalizing.[51]

Kirby’s predictions about radiation ended up coming true. Not in the exact way he described of course, but the general concept was true: radiation can make us stronger, more flexible, more dangerous and invisible. Today, for example, mobile technology relies on microwave radiation for both wifi and the atomic clocks that drive global positioning. Mobile technology makes us stronger (we can more easily work in larger groups), more flexible (we can do more things), more dangerous (we can organise fighters) and invisible (we can do it almost undetected).

All of this is just from microwave radiation: radiation in the wavelength around one centimetre. Imagine how much more will be possible once we improve our understanding of the much shorter wavelengths produced by atomic radiation. At present atomic radiation cannot be very precisely targeted, so it is most useful for killing cancerous cells (that is, cells that grow too quickly). Researchers can now switch molecular triggers on and off using radiation[52], which promises more precise control. Imagine what might be possible after another fifty years of research, when the switching on and off of molecules is routine along with splicing genes from one place to another. In Challengers of the Unknown issue 3, Kirby explained that these superpowers were simply gene manipulation by highly advanced alien societies. Kirby was simply looking ahead.

A different way to define Kirby’s story is not as hard science fiction, but as what Tolkien calls a “fairy story”. Tolkien defines this as follows:

A “fairy-story” is one which touches on or uses Faerie, whatever its own main purpose may be: satire, adventure, morality, fantasy. Faerie itself may perhaps most nearly be translated by Magic—but it is magic of a peculiar mood and power, at the furthest pole from the vulgar devices of the laborious, scientific, magician. [53]

That is, any story that involves something amazing and unusual. Or, as Tolkien puts it, a story involving “Marvels”. Tolkien says that a story about Marvels should give no hint that it is not real. Otherwise we have a lesser or debased form:

It is at any rate essential to a genuine fairy-story, as distinct from the employment of this form for lesser or debased purposes, that it should be presented as “true.” The meaning of “true” in this connexion I will consider in a moment. But since the fairy-story deals with “marvels,” it cannot tolerate any frame or machinery suggesting that the whole story in which they occur is a figment or illusion.

To clarify, Tolkien rejected the fake kind of fairy story. So did Kirby:

I didn’t want to tell fairy tales. I wanted to tell things as they are. But I wanted to tell them in an entertaining way, and I told it in the Fantastic Four.[54]

Kirby said his stories were real:

My stories were true. They involved living people, and they involved myself. They involved whatever I knew. I never lied to my readers. [...] If you analyze them, you'll find that I'm not really fictionalizing.[55]

Tolkien explained how fairy stories can and should be real: they should be internally consistent, and also reveal truths about the real world:

Probably every writer making a secondary world, a fantasy, every sub-creator, wishes in some measure to be a real maker, or hopes that he is drawing on reality: hopes that the peculiar quality of this secondary world (if not all the details) are derived from Reality, or are flowing into it. If he indeed achieves a quality that can fairly be described by the dictionary definition: “inner consistency of reality,” it is difficult to conceive how this can be, if the work does not in some way partake of reality. The peculiar quality of the ”joy” in successful Fantasy can thus be explained as a sudden glimpse of the underlying reality or truth. It is not only a “consolation” for the sorrow of this world, but a satisfaction, and an answer to that question, “Is it true?” The answer to this question that I gave at first was (quite rightly): “If you have built your little world well, yes: it is true in that world.”[56]

How can a fairy story tell us truths about the real world? By focusing on simplicity:

Fairy-stories deal largely, or (the better ones) mainly, with simple or

fundamental things, untouched by Fantasy, but these simplicities are made all the more luminous by their setting. For the story-maker who allows himself to be “free with” Nature can be her lover not her slave. It was in fairy-stories that I first divined the potency of the words, and the wonder of the things, such as stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; house and fire; bread and wine.[57]

Incidentally, Tolkien uses Thor as an example of a story about marvels. We could also give the example of the Human Torch: in the popular Alex Ross book “Marvels” the story of marvels begins with the Human Torch.

Tolkien warns against thinking such marvels are for children:

It is true that in recent times fairy-stories have usually been written or “adapted” for children.

But so may music be, or verse, or novels, or history, or scientific manuals. It is a dangerous

process, even when it is necessary. It is indeed only saved from disaster by the fact that the

arts and sciences are not as a whole relegated to the nursery; the nursery and schoolroom are merely given such tastes and glimpses of the adult thing as seem fit for them in adult

opinion (often much mistaken). Any one of these things would, if left altogether in the

nursery, become gravely impaired. So would a beautiful table, a good picture, or a useful

machine (such as a microscope), be defaced or broken, if it were left long unregarded in a

schoolroom. Fairy-stories banished in this way, cut off from a full adult art, would in the end

be ruined; indeed in so far as they have been so banished, they have been ruined.[58]

To summarise, the Fantastic Four, like Thor and others, is what Tolkien calls a fairy story, because it deal with Marvels in the real world. A good writer will make it totally believable, focus on simple concepts, and not aim it at children in particular.

Throughout this book I argue that Kirby is concerned with realism, he focuses on how people react to conflicts at their simplest level (in the moment, shorn of all details) and he deals with adult topics like survival, science, and sexual equality. In contrast, Lee avoids realism, he deals with surface appearances,[59] and simplifies stories to be more suitable for children. It follows that, by Tolkien’s measures, Kirby was a good writer and Lee was a bad one.

On the topic of page 7 and bad writing, long-time fans of the Fantastic Four may remember a synopsis printed in issue 358. It first appeared over twenty years after Fantastic Four 1, in the 1980s, when fans were starting to question whether Lee really invented these characters. So Lee produced a typewritten manuscript that he said was his original script. I examine it in detail in appendix 4, but here is the part that’s important for page 7. I scanned it from issue 358. Like I said, all the evidence you need is in the comics themselves:

Lee said that the Human Torch could only flame on for five minutes, and then had to wait until he became excited before he could flame on again, and that would be at least five minutes later. But now look at page 7 of the comic:

The Torch is chased by planes sent by Washington “before the hour is out”. That is, closer to an hour than five minutes. “So what?” you may ask, Lee changed his mind and the story was better for it? But that’s the point, The original plan was a bad idea from the start. Anybody who was used to creating stories would know that a guy who can only flame on for five minutes would be very limiting to the stories. Lee just wrote it without thinking it through. We see that again and again in Lee’s writing.

And on that topic of not thinking it through, why was the Torch flying around Central City for nearly an hour? He was already in the city, close enough to Reed to see the flare gun, and had to get there in a hurry. How long would it take to fly across a typical city? A minute? Five? Ten if he took the long route? Lee’s dialog makes no sense when we think about it. Yet the art not only tells the story on its own, but makes more sense.

The art looks like New York, one of the biggest cities in the world. Johnny knew the others would also have to reach Reed, so he may have taken a long route round the coast to scout for problems on his way. At the height of the cold war, such as 1961, a bomber could be scrambled in two minutes.[60] The nearest jets were probably at Stewart National Guard base, 55 miles to the north.

Given their expectation that this could be a Russian nuclear attack on New York City, they would have pushed the jets to their limits. So reaching Johnny within ten minutes is reasonable. The art shows he was then directly above Reed’s location. A ten minute journey fits perfectly and adds to the drama: who would reach their goal first, Johnny or the planes?

You are probably thinking “he takes this way too seriously!” And that is why Lee’s dialog is so damaging. Everything about the story could have happened in real life. But generations of readers, raised on Lee’s dialog, find it impossible to imagine these stories as anything but silly.

By page 8 the art showed us a fascinating and horrifying view of Johnny storm. It revealed his character through his choices: how he throws himself into danger, sometimes at the cost of destroying what he loves:

First, the art showed that he loves cars, and spent a long time working on them. But in responding to his call he destroyed one of the cars he was working on.[61]

Next we saw him destroying planes, almost killing several people.

Later in the story we will see him set fire to a forest

Look at that face. He is never happy when he flames on. Yet Lee’s dialog says he loves it.

Finally we see him cause the caves around him to collapse, which may or may not contribute to the radioactive materials exploding..

After destroying the planes we saw him hunted by a heat seeking missile, and without miraculous intervention he would have been dead.

Next we saw that his flame suddenly ran out, leaving him falling hundreds of feet to be smashed onto the concrete below.

This is a man who causes destruction on a large and chaotic scale. His life expectancy is measured in minutes, not years! And the life expectancy of those who come close to him him isn’t much better.

At least, that is the horror story told by the art, a story set in the real world, a story of what could happen if radiation did unimaginable things to our bodies. What kind of person is Johnny Storm that he chooses to burn up like that? He is a fire starter in the biggest way! Through these few acts we see his character. And we get an idea of the underlying message of the story, the horror and danger when radiation goes wrong.

We get all that from the art. But the text, on the other hand, is literally a different story.

The text captures almost none of this tragedy. The text says Johnny loves flaming on! The text does not have Johnny react to destroying his beloved car. The text underplays the destructive horror: Johnny blames the planes for being destroyed and says it's their fault! And when he falls from the sky he doesn't even have any dialog: the text is a passive and detached description.

In fact the whole of page 8 is almost all verbose description of what we can already see: it is all about how the reader wonders what happens next, there is no insight into how these characters think or feel.

In summary, the art shows more intense horror and more insights into characterisation. But the text reduces both. Once again we see that the Kirby's art creates a rich and dynamic story and Lee's text waters it down.

On page 9, Ben's anger clouds his judgment, and he will eventually pay a high price.

Ben and his anger become the heart of the Fantastic Four, it is what set them apart from other comics where characters always seemed to be friends. A person’s attempt to control their anger was a common theme in Kirby’s work over the years. The theme is perhaps best known from the Hulk, but here a fan talks about Kirby’s 1948 story “Disgrace”:

“Disgrace!" from Young Romance July 1948, which I believe stands alongside the best of anything Kirby ever wrote. At first I was struck by the language, so distinctly his:

"Although I was born and raised on the surface of the earth, I had never seen the full brightness of the sun, or felt the clean, fresh touch of the air...The town of Coalville was a dark mine shaft...and in its depths, my soul moved...harnessed in the yoke of resignation."

The story contains his greatest theme, which he has explored many times in works such as The Pack, The Frog Prince, and with The Thing and The Hulk, et al: Man's violent nature and the struggle to overcome those base instincts.[62]

Usually Kirby didn’t have the space to explore repressed emotions in detail, as a typical story was often just eight pages. But when he did have the space his work showed great sophistication. Take for example his story The Frog Prince (circa 1950), about a man’s frustration:

Clay Chapman is both the title character and the protagonist in Kirby's play "The Frog Prince." Chapman had been running around town as an egotistical golden boy until his face is scarred in an automobile accident. Like Doom, Chapman is unable to deal with his spoiled profile even though his scars are not grotesque.[63]

When Kirby co-created the romance genre in comics, he was very much at home with the human, emotional side of stories. In contrast, Lee did not have a track record of subtlety or characters with real human emotion: it’s not even clear how much Lee wrote at all. His dialog in Fantastic Four 1 does not suggest a writer capable of subtlety or realism.

On this page we have first evidence of major changes to the book before publication.

Kirby’s stories always had splash pages when the story took a new turn. It didn’t matter how relatively minor the change was, or how long it was since the last one, if a new section of the story began we always got a splash page.

This is not an idea Kirby just invented half way through issue 1 and then used in later issues. It was normal for his previous comics, like the Challengers. Here is the start of Challengers of the Unknown issue 1. The story begins the same way as the Fantastic Four origin, with the team standing around discussing a problem. But first we have the splash page. But where is the splash page for the Fantastic Four’s origin?

Here are three more clues that suggest a splash page has gone missing:

The apparent loss of the splash page is is the first of many hints that the book was changed before publication. Later hints will be stronger.

The art shows four people involved in a space flight. They oppose protocol and force the flight to leave earlier than planned. So far this is a realistic possibility. In the early days of spaceflight everything depended on one person. In Russia this man was Sergey Korolyov. In America it was Wernher Von Braun.

Everyone in the ground crew would hold these men in awe. If either of these men had decided to launch a rocket earlier than planned then the ground crew would have followed orders. They would of course risk an army of angry bureaucrats a few hours later: but if they succeeded it wouldn’t matter.

As for the location of the spaceport, the art suggests the team are based in New York. Kirby had just finished Sky Masters, which included features on the real world space race, so Kirby would be well aware of launch facilities near the city where he lived. The closest launch site to New York was Wallops Flight Facility, Delmarva Peninsula, Virginia, established 1945.

There have been over 16,000 launches from the rocket testing range at Wallops since its founding in 1945 in the quest for information on the flight characteristics of airplanes, launch vehicles, and spacecraft, and to increase the knowledge of the Earth's upper atmosphere and the environment of outer space. The launch vehicles vary in size and power from the small Super Loki meteorological rockets to orbital-class vehicles.[64]

So the art shows a story that could be real. But the dialog turns this into something unrealistic: a scientist decides to take his girlfriend and her kid brother into space!

This may be a fun idea for children, but it ruins the story for adults. If the dialog had better reflected the story then it could have worked on both levels.

On page ten we see the first indication that the team are gaining superpowers. Except that at this stage this is simply a horror story.

We have seen (and will continue to see) that Lee aims his stories at children, so this horror story was not created by Lee.

Who had the idea for superpowers? At this point (1961), Kirby had just introduced a new, more realistic kind of superhero: the Challengers. He had also just created more conventional superheroes, in “The Fly”...

...and the Double Life of Private Strong.

Lee later said that superheroes were his idea, based on DC’s recent book Justice League of America. However, Lee’s story falls apart on closer inspection.[65] For example, a look at the timeline suggests that Kirby was responsible for kick-starting the superhero era that became the silver age of comics.[66]

The Fantastic Four’s superpowers were practically the same as he had recently given Rocky in Challengers issue 3 (flame, invisibility, size changing and great strength). Kirby was just continuing what he was already doing.

By 1961, Lee had been making comics for over twenty years. His stories sold poorly and were by definition mediocre at best.[67] But when Lee started a new book with Kirby, suddenly his plotting and characters improved. This improvement ended the moment that Kirby left.[68] Lee explained it this way: one day he just decided to concentrate, and then his writing improved.

It was time to start concentrating on what I was doing — to carve a real career for myself in the nowhere world of comic books.[69]

However, right from page 1 (Central City, Reed’s hesitancy) we have evidence that Lee was not concentrating as much as he might. Page 11 has some clear examples of carelessness.

Page 11 contains not one but two typos: “completely” is spelled “completly” and “invisible” is spelled “invinsible”. Typos elsewhere include on page 16, where “countless” is spelled “coutless”, and on page 17, where “equatorial” is spelled “equitorial”.

Anybody can make a typo, and perhaps a great writer, engrossed in a stream of consciousness, would make more. But didn’t he read it back afterwards? Lee was an editor, and an editor’s job is specifically to spot these things. And this was a first issue: in Secrets Behind the Comics, Lee claimed that “when a comic strip is born, the greatest effort is made to see to it that the comic strip is perfect!”

Not only was this his “greatest effort” but Lee claimed to be “concentrating” more than ever before in his career. Something does not add up. As Kirby argued later, how could Lee come up with this comic when Lee “could hardly spell”?[70]

Some typos might be blamed on a letterer: errors like repeated words can be signs of concentrating on the letters and not the meaning of the sentence. But “equitorial” is harder to explain that way. If Lee spelled it right, why would a letterer get it wrong?

A person is very unlikely to get “equitorial” wrong if they understand the meaning: from “equator”, from the word “equate”. “Equitorial” just screams out that it is wrong as soon as it is written. Whoever made that typo wasn’t a science fan, that’s for sure. On the same page Lee didn’t recognise a piece of scientific equipment, so he is the prime suspect. Either way, as an editor taking “the greatest effort” he should not let four typos pass him by.

Other comics of the time also imply that Lee had trouble spelling. How did he miss the word “Pharoah” in large letters on a cover, twice? Even if he can blame someone else, as editor he should have spotted those.

There are plenty of indications that Lee didn’t always concentrate. He admitted that he gave characters alliterative names (such as Reed Richards, or Sue Storm) because he tended to forget who was who:

"It would be hard for you to believe this, because I seem so perfect: I have the worst memory in the world," Stan said. "So I finally figured out, if I could give somebody a name, where the last name and the first name begin with the same letter, like Peter Parker, Bruce Banner, Matt Murdock, then if I could remember one name, it gave me a clue what the other one was, I knew it would begin with the same letter."[71]

This recollection was not just Lee being modest. Bruce Banner spent a whole issue being called Bob Banner, and in the first Spider-Man issue, Peter Parker (named in Amazing Fantasy 15) became “Peter Palmer”.

Is this the sign of a writer who cares about his characters and their unique situations and personalities?

On page 12 we come to the heart of the Fantastic Four: the serious fighting between Ben and the other men. This is what made the Fantastic Four different from other comic books of the time. It made the book stand out as more alive, more real, more interesting. Whoever added this detail was responsible for making the book a hit. But was it Lee or Kirby?

In several places in Fantastic Four issue 1, Kirby’s art depicts violence and Lee’s text either tones it down or misses the reason.

On pages 4-5 we see Ben destroying a door he previously walked through, then in an aggressive pose to a police officer, then tearing up the streets, then destroying a car, and people running in panic. The dialog could have gone either way, but Lee chose to make it all seem accidental, just a guy in a bad mood, rather than someone who maybe hated the world and had the power to do something about it.

In every appearance of the Torch we see violence and danger, even horror, but Lee tones it down.

On pages 20-21, discussed later, Lee misses the significance of the battle.

On page 23, discussed later, Lee again misses the significance of the battle.

Each of these examples is subtle. Lee did not make enormous changes, but his changes were all in one direction: Kirby creates stories with conflict everywhere: in battle, in romance, inner conflict with yourself, and so on. Lee then tones down the conflict.

In every case the conflict is seen in the art more than in the dialog. So if we are asking who created the conflicts between the characters, it had to be Kirby.

Both Lee and Kirby have described their version of how the Fantastic Four came about. We could examine their particular claims (see appendix 2) but we don’t even need to go that far. Whenever Lee talks about the origin of the Fantastic Four he talks like this:

After about 20 years on the job, I said to my wife, "I don't think I'm getting anywhere. I think I'd like to quit." She gave me the best piece of advice in the world. She said, "Why not write one book the way you'd like to, instead of the way Martin wants you to? Get it out of your system. The worst thing that will happen is he'll fire you -- but you want to quit anyway." At the time, DC Comics had a book called The Justice League, about a group of superheroes, that was selling very well. So in 1961 we did The Fantastic Four. I tried to make the characters different in the sense that they had real emotions and problems. And it caught on. After that, Martin asked me to come up with some other superheroes. That's when I did the X-Men and The Hulk. And we stopped being a company that imitated.[72]

Lee talks about himself for half the time. Then he talks about the surface details: these characters have superpowers. He then talks about what made them different in the most abstract way: they had real emotions and problems, but which emotions? Which problems? Why should a reader care? Now compare how Kirby describes what happened:

The idea for the F.F. was my idea. My own anger against radiation. Radiation was the big subject at that time, because we still don’t know what radiation can do to people. It can be beneficial, it can be very harmful. In the case of Ben Grimm, Ben Grimm was a college man, he was a World War II flyer. He was everything that was good in America. And radiation made a monster out of him–made an angry monster out of him, because of his own frustration.

If you had to see yourself in the mirror, and the Thing looked back at you, you’d feel frustrated. Let’s say you’d feel alienated from the rest of the species. Of course, radiation had the effect on all of the F.F.– the girl became invisible, Reed became very plastic. And of course, the Human Torch, which was created by Carl Burgos, was thrown in for good measure, to help the entertainment value..[73]

We can’t rely entirely on memory of course, but note how Kirby talks about the underlying motivations, the feelings, what made each individual character different. Kirby knows what drives the characters as individuals, and hence where conflicts would arise. So who is more likely to have written these conflicts? Lee or Kirby?

Lee’s earlier work was all aimed at younger readers and had no serious continuing stories, as he admitted himself in an earlier quote. So there were no serious internal conflicts. A typical Lee series was Millie the Model:

This follows from Lee’s personality: while Kirby is a natural fighter, Lee’s style is to be likeable and light hearted. It is notable that years later, when Lee took over writing Spider-Man,[74] Peter Parker became more popular and had more friends. He still had self doubt - this seems to be Lee’s contribution to the character - but not the savage hatred of friends that we see with Ben Grimm, Rocky Davis, etc., or even the hard edge of the early Ditko Spider-Man. Kirby fought in the war and struggled his whole life. He understood conflict. But Lee always had a much easier life, ever since his uncle gave him a job as a teenager. It is only natural that Lee’s work would tend toward the frivolous and fun with just the occasional self doubt.

What we see here is what we saw in Kirby’s Challengers of the Unknown issue 3. In the story Rocky (the character like Ben Grimm) tests an experimental space capsule, travels to the edge of space, and returns with the ability to turn invisible, flame on, change his body size and use great strength. The experience gave him a murderous hatred of his former teammates, and he could only be calmed by June (the Challengers’ equivalent of Sue).

For even more parallels, look no further than Kirby’s romance and crime books.

Look at every time Ben Grimm becomes angrily violent in the early fantastic Four. In every case, the art (and sometimes, as in this case, the dialog) shows it is about losing Sue Storm.