homeBritain in the 1970s

The greatest decade in the history of the world

1970-1979 was measurably the greatest decade in the history of the world. It had:- the greatest freedom

- the best year on record (1976)

- excellent economic growth

- a great reduction in violence

- and much more.

You have probably heard the opposite. If you read newspapers you would believe the world was falling apart. Let's look at what happened, and why the newspapers reported it as they did. I will focus in Britain, the country I know best, but a similar story could be told for the USA and other nations.

The basic idea

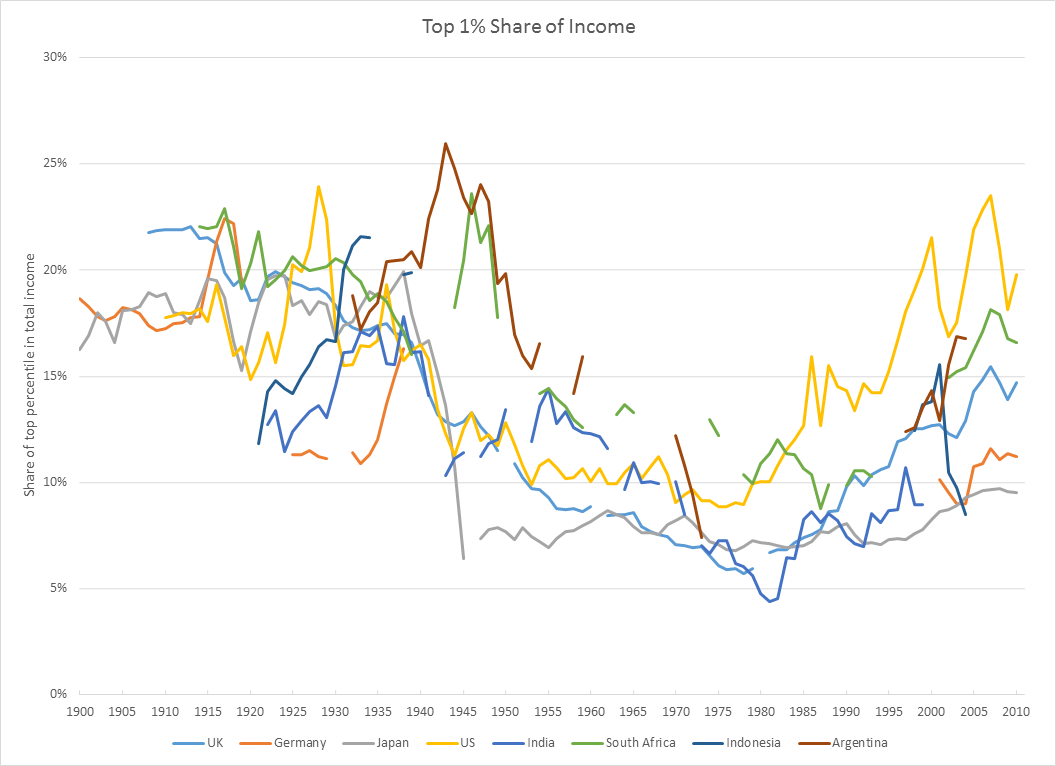

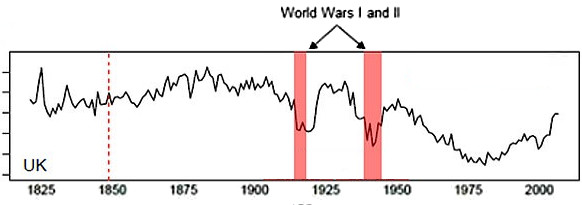

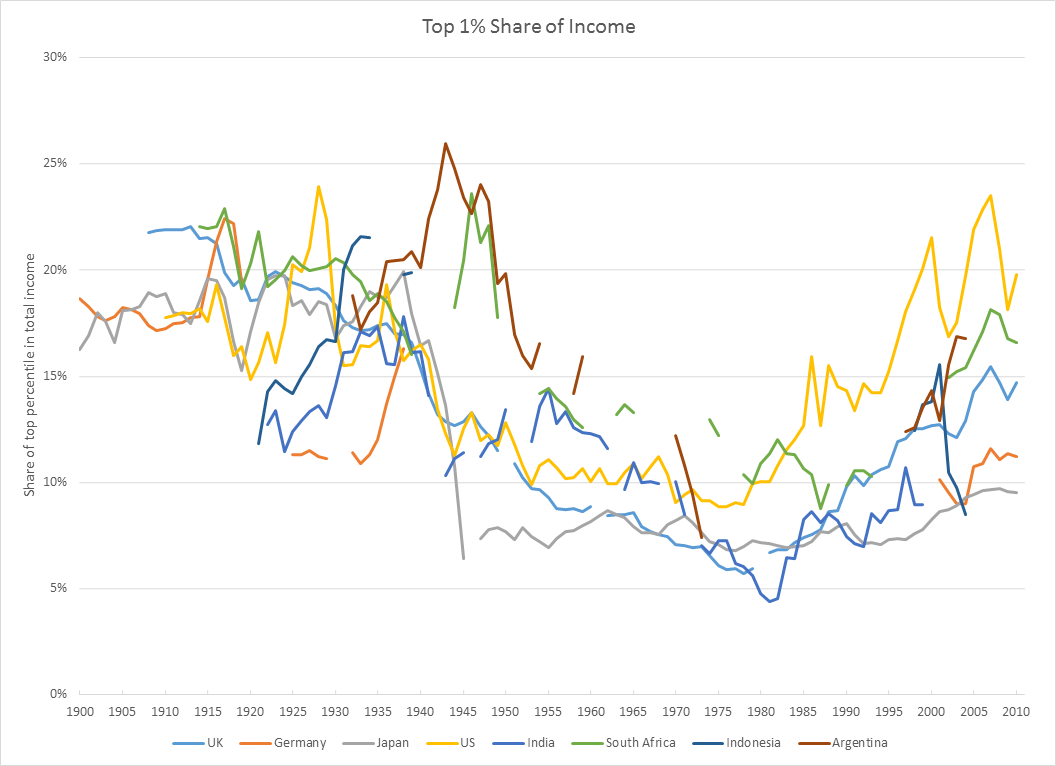

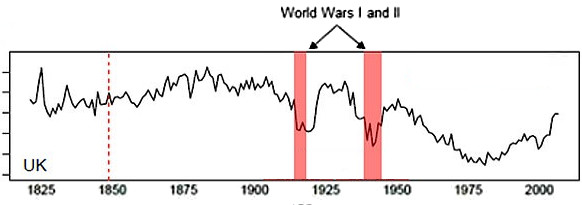

Thomas Pickety, in his book "Capital in the Twenty First Century", traces the distribution of capital throughout history. For most of history society has been extremely unequal. But between 1917 and 1978 (roughly), people were gradually becoming more equal. This means that the 1970s was probably the most equal time in history (and certainly the most equal time with access to modern technology).

(Image: "Bkwillwm", via wikipedia)

Equality matters because, even if you have money, if somebody else has a lot more, then they make the laws. So you get the life they want, not the life you want.

Now for the details.

(Image: "Bkwillwm", via wikipedia)

Equality matters because, even if you have money, if somebody else has a lot more, then they make the laws. So you get the life they want, not the life you want.

Now for the details.

1970: economic growth

This is the most important point. In the 1970s the economy grew. This matters because life was better: you could stand up to your boss - through strikes you had real power. People say "you can't do that, the economy won't work." And yet it worked. When people tell me that the rebelliousness of the seventies were bad for the economy, I feel like Galileo, being told the Earth cannot possibly move round the sun. And yet it moves!

The system worked, because it invested in education and basic needs, allowing each person to challenge any ideas and reach their potential. Despite the oil crisis, competition from Asian tiger economies, and some terrible inflation causing monetary policy in the early 1970s, the system was robust and continued to grow. Who knows how much faster it would have grown once the massive North Sea Oil revenues began in 1979. But we will never know, because the system was abandoned for ideological reasons, the North Sea Oil money was squandered, and the country fell into recession in the 1980s instead.

Here are the figures for the British economy, quarter by quarter. It always grew, except for two periods: the oil crises in 1973 and 1979. But even including those blips, everybody was (on average) better off.

GDP per person (inflation adjusted)

1970 Q1 2,405

1970 Q2 2,460

1970 Q3 2,478

1970 Q4 2,493

1971 Q1 2,466

1971 Q2 2,494

1971 Q3 2,529

1971 Q4 2,530

1972 Q1 2,532

1972 Q2 2,595

1972 Q3 2,601

1972 Q4 2,646

1973 Q1 2,784

1973 Q2 2,795

1973 Q3 2,775

1973 Q4 2,771 Oil crisis (Arab-Israeli war reduces supply)

1974 Q1 2,704

1974 Q2 2,756

1974 Q3 2,785

1974 Q4 2,752

1975 Q1 2,761

1975 Q2 2,718

1975 Q3 2,713

1975 Q4 2,751

1976 Q1 2,798

1976 Q2 2,773

1976 Q3 2,799

1976 Q4 2,857

1977 Q1 2,864

1977 Q2 2,851

1977 Q3 2,874

1977 Q4 2,914

1978 Q1 2,927

1978 Q2 2,956

1978 Q3 2,987

1978 Q4 3,009

1979 Q1 2,984

1979 Q2 3,112 Oil crisis (Iranian revolution reduces supply)

1979 Q3 3,038

1979 Q4 3,069

1980 Q1 3,039

1980 Q2 2,984

1980 Q3 2,977

1980 Q4 2,943

1981 Q1 2,923

(Source: Office of National Statistics)

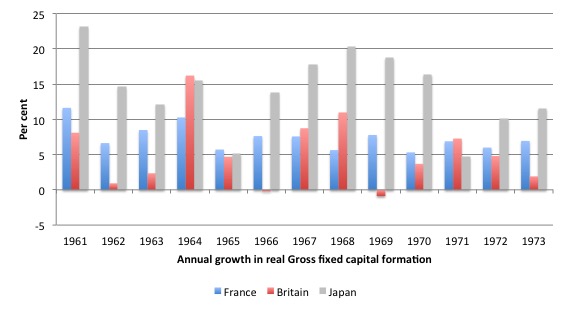

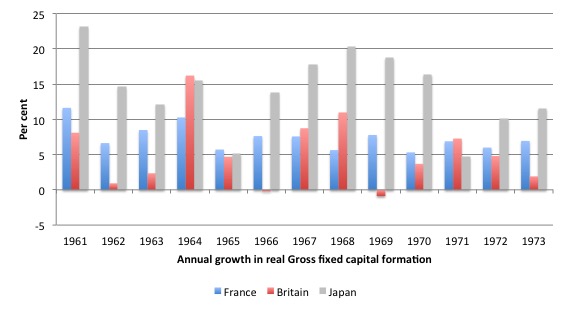

Germany and France were growing even faster, because they invested more in the 1960s. Britain simply did not invest as much, and consequently had slower growth.

(Image: Bill Mitchell's blog

In that time the share of investment going to wages (instead of capital) actually fell. "Over the decade to 1971, the wage share in GDP in Britain fell by 2.6 percentage points." (Bill Mitchell) So we cannot argue that 1970s inflation was caused by greedy workers. The inflation was entirely explained by printing too much money between 1970 and 1973, and then the oil crisis, as we shall see. If workers had not taken real terms pay cuts the inflation would have been much worse.

(Image: Bill Mitchell's blog

In that time the share of investment going to wages (instead of capital) actually fell. "Over the decade to 1971, the wage share in GDP in Britain fell by 2.6 percentage points." (Bill Mitchell) So we cannot argue that 1970s inflation was caused by greedy workers. The inflation was entirely explained by printing too much money between 1970 and 1973, and then the oil crisis, as we shall see. If workers had not taken real terms pay cuts the inflation would have been much worse.

1971: a kinder, more caring nation

In the 1970s we focused on two huge areas we had previously ignored: women's rights (i.e. fifty percent of the population) and environmental awareness. On women's rights, 1970 saw the Equal Pay Act, 1971 saw the founding of "Refuge" - the first of many refuges for battered women. For the first time the nation began to face up to domestic violence (ironically leading to an increase in reported incidents as more women came forward). Women's groups focused on making domestic violence a crime, leading to the Domestic Violence and Matrimonial Proceedings Act (1976) and the Domestic Proceedings and Magistrates' Courts Act (1978). Similar awareness raising led to more reporting of racist attacks, but also the start of more fairness. On the environment, 1971 saw "Friends of the Earth" first organised in the UK. Then in 1972 British meteorologist John Sawyer published the important report "Man-made Carbon Dioxide and the 'Greenhouse' Effect. Then the 1973 oil crisis made people realise that reliance on oil was unsustainable, and the book "Small is Beautiful" in America, which became the Bible for environmental thought. 1974 saw the Control of Pollution Act and Environmental Protection Act. 1975 saw the People Party re-brand itself as the Ecology party, and by 1979 it was the fourth largest party in the UK. Had this rate of progress continued, we would not be in the present climate crisis.

1972: less violence

Just as the increase in reports of domestic violence was a good thing - reflecting decreased tolerance - so the visible violence of 1972 reflected an overall net reduction in violence. Why? Because they both arise from a strong belief in self determination. A belief in self determination motivated hooligans to occasionally fight. A belief in self determination inspired the people of Ireland to want their country back (and for others to want to be part of Britain), and for the struggles that followed. But since those battles were at home they had relatively low fatalities. In Bloody Sunday, 14 people died. In hooliganism deaths are very rare. But the same belief in self determination made the government very reluctant to get involved in foreign wars. So when Henry Kissinger tried to persuade Prime Minster Callaghan to support regime change in Belize, Callaghan said no. And Callaghan was able to avoid conflict in the Falkland Islands simply by placing a royal navy vessel (HMS Endurance) along with a nuclear submarine and some frigates. And there were strong forces in his party (e.g. from Tony Benn and his supporters) to not use arms at all in Northern Ireland or the Falklands. So the 1970s were remarkable for how few conflicts there were. In contrast, Margaret Thatcher (not then in power) strongly supported Pinochet's coup in 1973 and soon after she came to power was at war in the Falklands. We are free to say it was not her fault, and it was just lucky that the 1970s were relatively peaceful. But the fact remains that they were relatively peaceful, and later decades were not. However we choose to explain it, the 1970s were the most peaceful decade for Britain and possibly the world. In Britain, a major 1970s conflict like Bloody Sunday killed 14 people. A major 1980s conflict like the Falkland invasion killed over 900 people. A major 1990s conflict like the first gulf war killed over 100,000 (perhaps divide that by the countries involved). A major 2000s conflict like the Iraq war killed far more than that. And since then wars have been ongoing wit drone strikes and guerilla war just apart of life. With global warming and refugees we can expect future numbers to be even higher. Making the 1970s look like an island of peace in an ocean of violence.

1973: fighting for honour in government

1972-1973 saw the "three day week", the government response to the miner's strike. The miner's strike was to stop the government from making others pay for its own mistakes. Back in the 1970s unions could still do this, resulting in a better nation. In later years, newspapers said the unions were the bad guys and the government was then free to do crush them. How did that happen? What mistakes had the government made? How could a miners' strike fix it? How could they then blame the miners anyway? Why did voters accept it and vote against their own interests? To answer those questions we need to understand the biggest economic story of the 1970s: inflation.

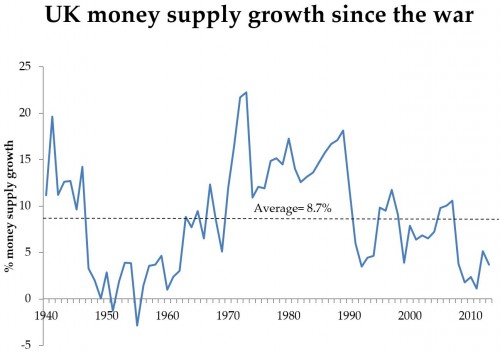

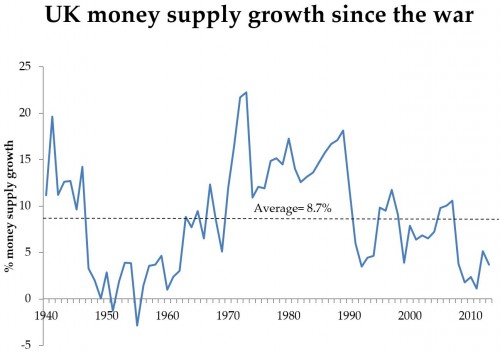

The 1970s saw high inflation, peaking at 26% in 1975. According to Milton Friedman, who won the 1976 Nobel Prize for economics for how work on this topic, inflation is always "a monetary phenomenon." (See his book "Money Mischief: Episodes in Monetary History"). That is, if you print more money then each note is not worth as much, and prices will increase. There was never a clearer example of this than Britain in 1972 and 1973. Between 1971 and 1973 the Conservative government had the disastrous "Competition and Credit Control" policy. They printing money, leading to money being worth a lot less: hence inflation. "In 1972, the money supply (measured by the M3 aggregate) rose by 27 per cent and in 1973, it rose by 28 per cent." (Mitchell). It takes a couple of years for big changes to feed through a large complicated economy, so 27% in 1972 and 28% in 1973 led to 26% inflation in 1975.

(It certainly did not help that global oil prices rose dramatically in 1973, but that was also a result of government choices. The government chose to ignore international law and greatly anger oil producers, so what did they expect? Obviously angry oil producers will fight back the only way they can, by raising the price of oil. Here are the details: After World War II, International law had clearly stated that Israel should have a homeland. So Palestinians were evicted from their land and Israel's borders were firmly set in law. Tough luck for the Palestinians, but the law is the law and they had to live with it. The law also established that, after World War II, it was no longer allowed to expand your borders by force. But when Israel did just that in 1967, Britain and America turned a blind eye. So in 1973 the Arab nations decided to enforce the law themselves, and try to force Israel to stick to its legal borders. The plan failed, and again Britain and America sided with Israel. Maybe we could say that Prime Minister Heath had no choice? His replacement, Jim Callaghan, showed that he did have a choice. Callaghan negotiated the 1978 Camp David Agreement between President Sadat of Egypt and Menachem Begin of Israel. Peace is possible, and the 1970s showed the way. But Heath chose to anger the oil producers so naturally they raised prices in retaliation.)

Instead of taking responsibility for his actions, Heath decided the workers should all take pay cuts (i.e. below inflation pay increases). So he introduced a bill in 1972 to weaken the power of the unions. The unions felt it was wrong to make the poorest workers in the country pay for the mistakes of the richest, so the miners came out on strike. The shortage of coal led Heath to create the "Three Day "Week" where industry shut down for four days per week to save energy. And of course blame the miners for his problems. Eventually he had to pay the miners. if they had given in then he could have just printed even more money and done the same again. That is what economists call "moral hazard" - if you can do bad and somebody else pays, then you do bad again. The miners in 1973 prevented moral hazard. They kept the government from continuing to print too much money. Sadly, two years later, unions let their compassion take over. As we will see in 1975, they eventually agreed to a cut in wages, to pay for the effects of printing money. By that time the Conservatives had been kicked out, but they watched from opposition and learned the lesson. In that year, 1975, Margaret Thatcher became leader of the party. She was a fan of Friedrich Hayek, who recommended high unemployment as a way to scare workers into accepting lower pay. So when Thatcher got power she continued to print money.

(Image: Inflation Matters, using Bank of England data)

But first she crushed the unions so that when the real bills came due the workers would pay for them through longer hours, harsher conditions, cuts in social security, etc. The terrible results of her actions were hidden by the enormous windfall of North Sea Oil, a result of investment in the 1970s, a windfall that should have been invested in eduction and industry, but instead disappeared without trace.

(Image: Inflation Matters, using Bank of England data)

But first she crushed the unions so that when the real bills came due the workers would pay for them through longer hours, harsher conditions, cuts in social security, etc. The terrible results of her actions were hidden by the enormous windfall of North Sea Oil, a result of investment in the 1970s, a windfall that should have been invested in eduction and industry, but instead disappeared without trace.

Why did people blame the unions?

Newspapers need simple stories. Headlines about the money supply do not sell newspapers (except to accountants). People find it too complicated. Headlines about strikes and conflict are much easier to sell. So people saw a conflict without seeing its cause. It looked like the unions were just as bad as the government. In fact, the unions looked worse because if a striker does not empty your bin you notice the rubbish and the smell! But if agovernemnt prints too much money you are less likely to notice: you might even think "great! more money!" So unions will always tend to look like the bad guys.

Meanwhile, newspaper owners are of course employers. So they want lower wages. If a thousand workers can take one pound less, that is a thousand pounds in your pocket! As time went on, with more and more strikes (because of cuts in wages), it became easier and easier to print stories about bins not being emptied, and violent angry unions. In 1978, when the government broke its promise to stop cutting pay (in real terms) the number of strikes increased and the newspapers had enough pictures of unemptied bins to say the country was in crisis. So the public voted for the Conservatives to crush the unions. The result was lower wages and less pleasant work conditions. Which meant more money and an easier life for newspaper owners. So newspapers continue to criticise unions for striking, right to the present day.

1974: affordable housing

The 1974 Housing Act ensured that Britain had plenty of housing for everybody. If you could not afford a house, the council would help. And because of this increased supply, nobody needed to pay more than they wanted for a private home, so private housing was much cheaper as well. Simply existing was not enough to drive you into debt slavery.

1975: unions save the nations

The government's over printing of money caused massive inflation (see above). So the unions agreed to pay for the government's mistake by workers taking lower pay (i.e. less than inflation, i.e. a real terms cut). This "Social Contract" was set to last from July 1975 to August 1977. The unions saved the nation from the government: inflation went down and the economy grew again.

Another example of saving the nation was in protecting us from dictators. As George Orwell pointed out in "Animal Farm", and as Lord Acton memorably put it in 1887, power corrupts."Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men."

The unions had the solution: everybody was allowed a say. Just visit any trade union meeting, or any old school Labour conference: everybody argues with everybody else. This is healthy. As long as people can revel, the system can work. Lech Walesa proved that five years later in Poland. Polish socialism had turned into dictatorship, and the workers were not allowed to strike. In 1980 he managed to gain the right to strike, and the dictatorship began to crumble.

1976: the best year in history

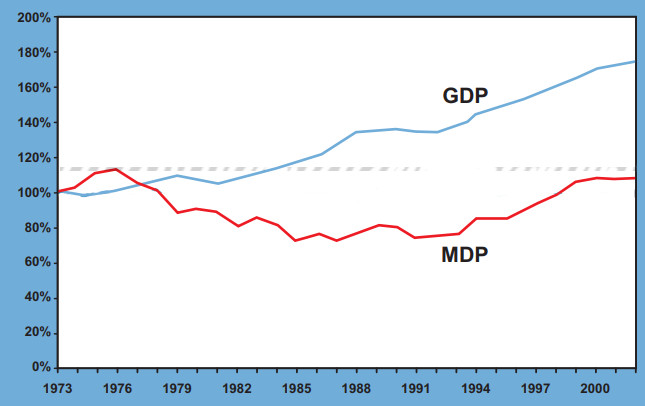

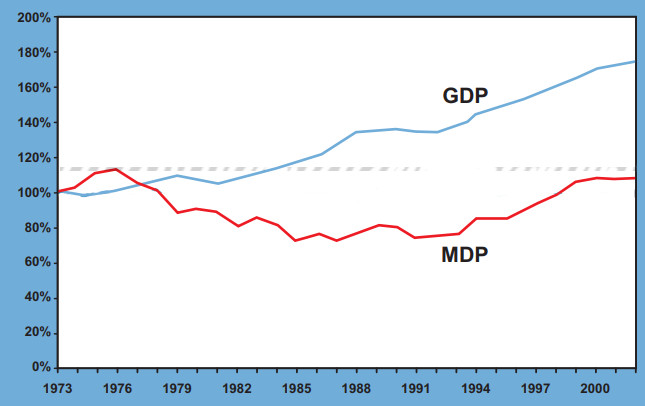

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the usual measure of a nation's success: it measures the value of everything a nation produces. The more it produce, the more it has of the things it wants. However, GDP does not include hidden costs. According to GDP, if you steal money or poison the planet or destroy all raw materials that counts as success. So to counter this, the New Economics Foundation also measured environmental costs, social costs, resource depletion and the cost of general risk taking. When combined these with GDP it creates MDP - "Measure of Domestic Progress" - and found that 1976 was the best year in which to live.

Given that Pickety showed that equality had been improving since around 1917, and before that we lacked modern technology, and that equality has declined since 1978 with technology giving ever greater economies of scale to the super rich, it is unlikely that any other year will ever beat 1976. Unless you happen to be a multi billionaire.

In the reports of this press release, it was often described as measuring happiness, but strictly speaking it measures well being. If books are any guide, the 1970s saw a decline in references to happiness. This could be because people could see what was coming - 1970s movies were often dystopian. Or it could mean people were being more realistic: when things are very bad we tend to buy books to cheer us up, but when things are looking good we feel strong enough to face the remaining problems. So for example the focus on women's rights and the environment. Those books would be very depressing reading, but actually reflect a movement to finally make things better.

Given that Pickety showed that equality had been improving since around 1917, and before that we lacked modern technology, and that equality has declined since 1978 with technology giving ever greater economies of scale to the super rich, it is unlikely that any other year will ever beat 1976. Unless you happen to be a multi billionaire.

In the reports of this press release, it was often described as measuring happiness, but strictly speaking it measures well being. If books are any guide, the 1970s saw a decline in references to happiness. This could be because people could see what was coming - 1970s movies were often dystopian. Or it could mean people were being more realistic: when things are very bad we tend to buy books to cheer us up, but when things are looking good we feel strong enough to face the remaining problems. So for example the focus on women's rights and the environment. Those books would be very depressing reading, but actually reflect a movement to finally make things better.

(Image: Warwick University press Release)

(Image: Warwick University press Release)

1977: the economy was stronger than we thought

With all the doom and gloom from newspapers and employers (i.e. anyone who would benefit from tax cuts, cheap loans and lower wages), the government in 1976 had expected the worst. Maybe the workers really were at fault? What if the economy got so bad that the government could not pay their bills? So they went to the International Monetary Fund for a loan of $3.9 billion, just in case. But after they took the money (and all the strings attached that hurt the poor), it turned out they did not need the loan after all. Inflation was going down, employment was going up, tax receipts up, costs down... the economy was stronger than they thought. They had expected to need total borrowing of 10.5 billion, but it turned out to only 8.5 billion. And the economy continued to improve so they balanced the books in 1977, before the IMF loan even took effect. And paid back the loan in 1978. It turns out that workers standing up against pay cuts is good - presumably it stops a race to the low skilled bottom. And a government that allows people to disagree ends up making better decisions. But those who want tax cuts, cheap loans and low wages will of course argue otherwise.

1978: higher output per person

By 1978 inflation was down to ten percent and still falling. Workers had lost so much due to below-inflation pay rises that they at least did not want to lose any more this year, now that the crisis was over. This of course meant a ten percent rise just to stay behind, not to catch up. But the government decided to limit pay rises to five percent, ensuring workers lost even more. In economics this is called "moral hazard": as long as rich people can do stupid stuff (like governments and banks causing inflation) and make poorer people pay for it, what is to stop them doing the stupid stuff again? Besides, the lower paid workers cannot afford constant real term pay cuts, as they have to pay their bills. So they had no choice but to strike. The worst period of Striking - winter 1978-79 - became known as "The Winter of Discontent":

"In January and February 1979, almost 30 million working days were lost, more than three times the whole of the previous year."

Is 30 million lost days a big number? Well, the working population was about 20 million people so on a typical bad year there is one day's lost production per year. Or, one half of a percent of the nation's potential work was lost. And on a normal year it was much less. The following year (1979) Margaret Thatcher came to power and revolutionised the economy. She used legislation to reduce the number of strikes, and also increased unemployment from 5 percent to more than 10 percent. That is, to save less than one half a percent of output, she lost more than five percent of output. Since then unemployment has gone down, but that required them to change the definition of unemployment, and also make it so unpleasant that a lot of people take jobs that waste their potential. Which supports the real story of the 1980s: efficiency losses. The biggest economic change of the 1980s was the number of women entering the workforce. There are now over 30 million people in the workforce, yet the rate of economic growth is only marginally higher than in the 1970s. That is, output per person must have plummeted.

1979: a nation of heroes

We have seen that governments like to print extra money for themselves. And this is a terrible idea! And making somebody else pay (through lower wages) it is even worse: it is "moral hazard": the government just does it again!

So in the opening months of 1979 the ordinary people said "ENOUGH!" They said they would simply stop working until the government agreed to find another way to balance the books. One obvious way is to tax rich landowners instead. The land would then be used even more efficiently to pay the tax, so that pays the debts and makes the economy more productive. Or maybe the government can find some other ways: what are all these economics experts being paid for anyway?

Going on strike is a big sacrifice. It means you get no money (unless your union can scrape together a few pennies). It means employers and newspapers hate you. But if you don't do it you get a government that just prints money and makes the poor pay. You have to stop that for the sake of the whole nation. You have to be the hero. And in 1979 we had a whole nation of heroes, ready to take on the government and say "stop stealing from the poor!" It was a nation of Robin Hoods. It was a golden age of heroes.

Appendix: let's talk business

Some of the things that British people discovered (or invented) in the 1970s:

- DNA sequencing (by Frederick Sanger)

- the first test tube baby

- the digital audio player (by Kane Kramer)

- packet switching

- North sea oil

- one of the first handheld televisions

- gene splicing (by Richard R. Roberts)

- infrared remote sensing

- the tree shelter (to protect seedlings)

- a new way to detect spina bifida

- how a mother's smoking affects pregnancy

- teletext

- echo planar imaging (EPI) and other improvements to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- the portable defibrillator

- how the body produces endorphins

- the effects of poverty on learning difficulties

- The coaxial clock escapement mechanism

- the RSA cipher

- the first small pocket calculator (the Sinclair Executive)

- the first laptop computer (the GRiD Compass)

- stun grenades

- Hawking radiation

- Advances in quantum gravity (Hawking again)

- aperture synthesis (for better radio astronomy)

- the importance of omega 3 to the brain

- DNA sequencing (by Alec John Jeffries)

- modern bungee jumping

- and many more

This is what happens when you invest in education and encourage free thinking.

Notice what all this work has in common: people create science and music because they love doing it, not for the money. Sure, they need their basic needs met, but their passion is for the work. Why? Because the work does good! It makes our lives better! And yes, sometimes is makes a ton of money. But money is not the motivation. The motivation is love. Love of the idea, of creating, of making a better world.

If you are a worker, you make more wealth if you are passionate about your work. And if you are an employer you make more money is you find people who are as passionate about it as you are. And if nobody cares that much, and you cannot pay enough to make them passionate, maybe you should choose a different industry. Because ultimately our human needs are very simple: a few calories, some shelter. There is always a better and more interesting way to achieve these: you don't have to be stuck in some rat race fighting with workers or bosses who don't like you.

The government followed this principle after 1945 by invested heavily in houses and universities and free education, and it paid off. And the future after 1979 was going to be very bright indeed: because 1979 started to see North Sea Oil revenues: up to 12 billion pounds of extra tax revenue every year! That is, three times the IMF bailout every year! Imagine what houses and laboratories and new ideas that could fund! But instead Margaret Thatcher was voted in, and the system of investing in people was abandoned, replaced by a system of chasing short term profit. the North Sea oil billions were wasted, free education was phased out, life was no longer fun, and the country entered a recession.

But what about those badly made British cars, you ask? Why weren't cars full of the usual British breakthroughs? It was due to tax incentives: people were going to buy British anyway for tax reasons, so why work harder? It was a government choice again. We got fantastic science and mediocre cars. But is that such a bad thing? Once a car gets you from A to B 99 percent of the time, very few people care to waste their lives chasing that final 1 percent. They would rather be creating beautiful objects that last for centuries, or painting pictures, or working with animals, or inventing things... or just having fun with their friends making a "good enough" car. Because that is the quality that really matters: the quality of life, the quality of enjoying your eight hours a day at work, and not being slave in some inhuman rat race.

All this talk of freedom and happiness might sound like madness. Surely business has to be cut throat? Surely you have to work harder and harder every year? No, actually you don't. You need to be passionate about what you do, to do the very best, or else just have fun. because life can be passionate, or fun, and gentle and kind with basic needs for all. And doing that the economy can still grow. The 1970s proved it.

I miss the 1970s.

home

(Image: "Bkwillwm", via wikipedia)

Equality matters because, even if you have money, if somebody else has a lot more, then they make the laws. So you get the life they want, not the life you want.

Now for the details.

(Image: "Bkwillwm", via wikipedia)

Equality matters because, even if you have money, if somebody else has a lot more, then they make the laws. So you get the life they want, not the life you want.

Now for the details.

(Image: Bill Mitchell's blog

In that time the share of investment going to wages (instead of capital) actually fell. "Over the decade to 1971, the wage share in GDP in Britain fell by 2.6 percentage points." (Bill Mitchell) So we cannot argue that 1970s inflation was caused by greedy workers. The inflation was entirely explained by printing too much money between 1970 and 1973, and then the oil crisis, as we shall see. If workers had not taken real terms pay cuts the inflation would have been much worse.

(Image: Bill Mitchell's blog

In that time the share of investment going to wages (instead of capital) actually fell. "Over the decade to 1971, the wage share in GDP in Britain fell by 2.6 percentage points." (Bill Mitchell) So we cannot argue that 1970s inflation was caused by greedy workers. The inflation was entirely explained by printing too much money between 1970 and 1973, and then the oil crisis, as we shall see. If workers had not taken real terms pay cuts the inflation would have been much worse.

(Image: Inflation Matters, using Bank of England data)

But first she crushed the unions so that when the real bills came due the workers would pay for them through longer hours, harsher conditions, cuts in social security, etc. The terrible results of her actions were hidden by the enormous windfall of North Sea Oil, a result of investment in the 1970s, a windfall that should have been invested in eduction and industry, but instead disappeared without trace.

(Image: Inflation Matters, using Bank of England data)

But first she crushed the unions so that when the real bills came due the workers would pay for them through longer hours, harsher conditions, cuts in social security, etc. The terrible results of her actions were hidden by the enormous windfall of North Sea Oil, a result of investment in the 1970s, a windfall that should have been invested in eduction and industry, but instead disappeared without trace.

Given that Pickety showed that equality had been improving since around 1917, and before that we lacked modern technology, and that equality has declined since 1978 with technology giving ever greater economies of scale to the super rich, it is unlikely that any other year will ever beat 1976. Unless you happen to be a multi billionaire.

In the reports of this press release, it was often described as measuring happiness, but strictly speaking it measures well being. If books are any guide, the 1970s saw a decline in references to happiness. This could be because people could see what was coming - 1970s movies were often dystopian. Or it could mean people were being more realistic: when things are very bad we tend to buy books to cheer us up, but when things are looking good we feel strong enough to face the remaining problems. So for example the focus on women's rights and the environment. Those books would be very depressing reading, but actually reflect a movement to finally make things better.

Given that Pickety showed that equality had been improving since around 1917, and before that we lacked modern technology, and that equality has declined since 1978 with technology giving ever greater economies of scale to the super rich, it is unlikely that any other year will ever beat 1976. Unless you happen to be a multi billionaire.

In the reports of this press release, it was often described as measuring happiness, but strictly speaking it measures well being. If books are any guide, the 1970s saw a decline in references to happiness. This could be because people could see what was coming - 1970s movies were often dystopian. Or it could mean people were being more realistic: when things are very bad we tend to buy books to cheer us up, but when things are looking good we feel strong enough to face the remaining problems. So for example the focus on women's rights and the environment. Those books would be very depressing reading, but actually reflect a movement to finally make things better.

(Image: Warwick University press Release)

(Image: Warwick University press Release)